In the first act of Glengarry Glen Ross, pairs of men in suits use bad words and sip hard drinks in a Chinese restaurant. This is the real estate business, a changing industry, and they’re desperate to keep their jobs by any means necessary. The lights are low and the music cheesy as each pair hatches a plan. There’s one to take the premium property leads, and another to bribe the office manager. It’s unclear which is legal, and which isn’t. But none of them feels right.

|

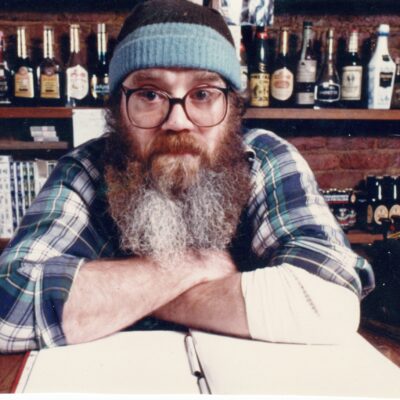

Mad men: The cast of Glengarry Glen Ross works diligently to close on opening weekend at Live Arts. |

For the second act these jagged bits and pieces—four real estate agents, the dupe, the office manager and a cop—are jammed into an office, where the drawers of a filing cabinet lay ajar. The premium leads, which were the only sure sales bets, have been stolen.

David Mamet based the wild game of foul-mouthed finger pointing on his experience as real estate broker in Chicago, and perhaps this is how Glengarry feels so distant, but so real. These characters, whose deafening humanity renders them almost superhuman, talk in a jargon equal parts familiar and alienating. (What exactly are “premium leads,” and why are they so important?) Here lies the peculiar power of David Mamet’s Glengarry: One walks away feeling clobbered by the gist, knocked down by the wind.

Director Boomie Pedersen gives the Pulitzer Prize-winning script the meat-and-potatoes treatment, with sparse, iconic set design—all the way down to the bottle of Kikkoman—artfully choreographed language and forceful performances from a veteran cast. Glengarry is Live Arts’ fourth Mamet production, which makes him one of that organization’s most produced playwrights. The relationship works.

Whether these characters are good or evil, they’re good capitalists, and the intimate Live Arts Upstage theater hangs moral unknowns in the rafters, out of plain view but where you can smell them. A cop metes out justice behind closed doors; the perpetual and amorphous threat of “Mitch and Murray,” the bosses, circles overhead; and the wife is always at home.

It is the last of these pressures that forces James Lingk (Bill LeSueur) into the mayhem of Glengarry’s second act. One can almost smell the sweat and talcum powder on Ricky’s (Michael Volpendesta) neck as Lingk, the consummate milquetoast, tries to gracefully renege on the deal. Slimy, yes. But Shelly Levene (playfully rendered by Jim Johnston) is the most slippery of these snakes. He brags and fawns in turn as he gains and loses the upper hand, and laments the changing industry that has come to reward performance instead of longevity; he only has the latter.

Kevin O’Donnell absolutely bludgeons the role of Dave Moss, the cast’s most conniving meathead. The theater tilts in his direction as he pounces about in the second act. His scene with George Aaronow (Harold Langsome), the plaid-wrapped wimp, might be the play’s most entertaining—if it weren’t for Mamet’s mesmerizing mess of a second act.

Much lip service has been paid to Glengarry’s relevance in the modern day. Twenty-five years have passed since its Broadway debut, and yet men still work on commission, seek to increase their share by depleting ours and cite in doing so the rules of the game. And really, it’s disheartening to have to share the real world with the likes of these characters. But bad things happen to some of them. All the more reason to, as Artistic Director John Gibson said, “Enjoy the fucking show.”