What a mixed blessing that Carey Mulligan’s stardom should begin here, with the transitory pleasure of an awards-season dido, veiled in the nostalgic mist of inevitable Audrey Hepburn associations and other more current modes of media infatuation. Certainly Mulligan wears the burden well, carrying An Education without hoarding it, and giving off enough dimpled radiance and girlish poise to indulge our fantasy that this furtively conventional coming-of-age period piece, about a teenager’s eye-opening romance with a much older man, be anything but common.

|

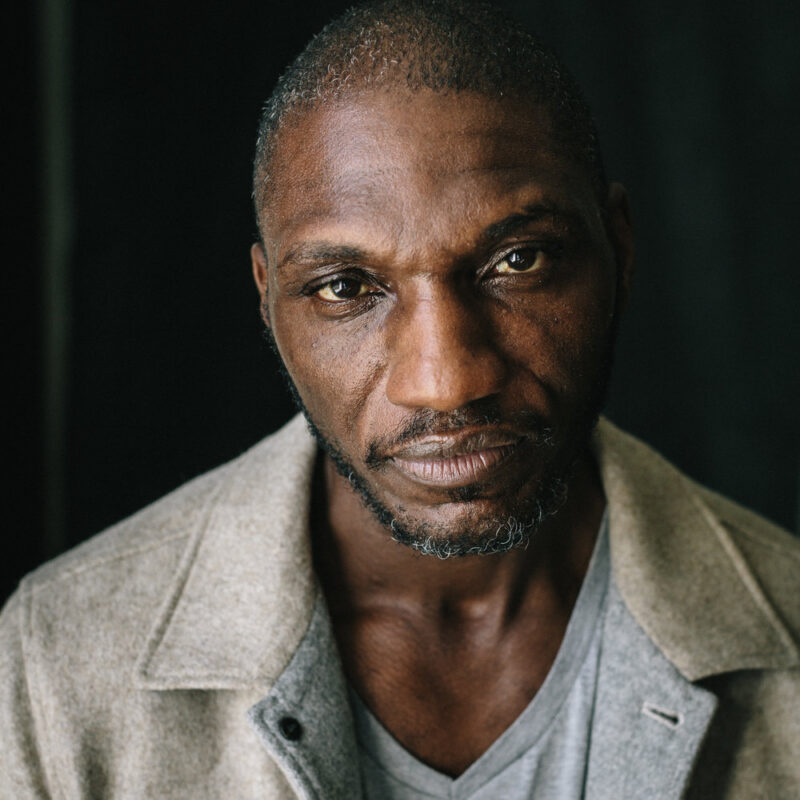

Jenny (Carey Mulligan) leans on her older lover, David (Peter Sarsgaard), in An Education, based on Lynn Barber’s memoir. |

As essential as Mulligan is to An Education’s charm, so is her given milieu: Britain, 1961, in tentative transition from shattered war ruin to swinging pop-culture concourse. The movie depends on our willingness to furbish any given tale of that transition with every benefit of our doubt. To that end, it helps having the lightly fictionalized adaptation of journalist Lynn Barber’s memoir handled so economically by director Lone Scherfig, who prefers that this education remain unsentimental, and screenwriter Nick Hornby, of High Fidelity fame, with his usual shrewd understanding of pop palatability.

Mulligan’s Jenny, a 16-year-old aspiring sophisticate of London’s suburban middle-class, is promptly revealed as the most alert girl in her school, maybe even the prettiest. Jenny’s parents, Jack (Alfred Molina) and Majorie (Cara Seymour), have determined that she’s bound for Oxford. The question is whether she’s bound to it. What exactly are her options?

Chief among the noticers of Jenny’s potential is one David Goldman (Peter Sarsgaard), a somehow vulnerably suave man of approximately twice her age who agilely offers her a whirlwind of concerts, fine dining, art auctions and trips to Paris—absolute manna for a girl like her.

Biding his time, David (or Sarsgaard, at least) wears his politesse like a mask. Initially he lets it be known only that he’s Jewish, that he has money, and taste, and intent—and that he understands how to play Jack and Majorie’s class envy to his own advantage. We wonder uneasily what it means that being with such a shady fellow so clearly lights Jenny up. But remember, this is a time and a place where ominous, omnipresent barriers of ethnicity and gender exacerbate the already thorny adolescent melodrama of yearning for social mobility. And so we also find ourselves rooting for her, on behalf of her entire generation, to mature into a symbol of self-determined liberation.

Scherfig doesn’t declare outright whether class can be taught, or bought; she reasonably avoids framing Jenny’s transformative experience as a straightforward journey from the promise of precocity into the weariness of wisdom. But something in the hurried denouement seems self-betraying.

Maybe it’s just the poignancy of Mulligan’s feasibly Hepburnesque refusal to dignify disenchantment. She pulls it off so fetchingly that we can only wonder what her future holds, and whether she’ll ever be allowed to graduate from our nostalgic ideal.