By Claudia Gohn

From April 1 to July 31 of this year, emergency teams responded to 27 opioid overdoses in Charlottesville—a 200 percent increase in cases compared to the same time frame in 2019, reports the Charlottesville Fire Department. Health professionals believe the stress of the pandemic is one factor responsible for the increase.

Other areas in the state are struggling with similar problems. Arlington County police issued a warning last week after five people died from drug overdoses in August. In Roanoke, police responded to twice as many fatal drug overdose calls this spring as they did in all of 2019, reports The Washington Post. And NPR reports that nationwide, overdoses are up 18 percent since the pandemic began.

The local increase in opioid overdose calls comes despite an overall decrease in the amount of emergency calls this year, says Lucas Lyons, the Charlottesville Fire Department’s systems performance analyst. Total emergency calls in the city were down 23 percent in the period from April to July 2020, compared to the same months in 2019.

“In general, 9-1-1 calls are down because of people’s fear of the pandemic and not entering the medical system,” says the Community Mental Health and Wellness Coalition’s Rebecca Kendall. “But there is an increase in Charlottesville in calls for overdose despite that.”

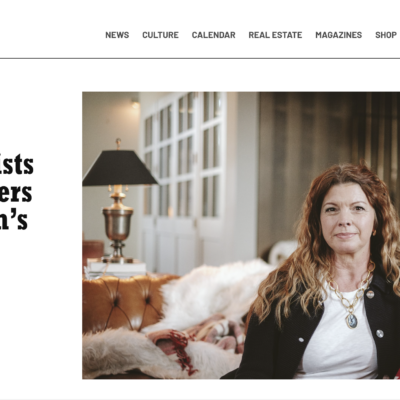

Virginia Leavell, chief of the Charlottesville-Albemarle Rescue Squad’s board of directors and director of Addiction Allies, a treatment center for people with opioid use disorder, attributes this increase to the isolation and decreased access to in-person recovery services many have experienced during the pandemic. “I think when we are looking at why there is some increase, it’s somewhat predictable, right?” Leavell says. “We’ve taken away the support structure and we’ve added a whole lot of stress.”

Leslie Fitzgerald, care coordinator for Region Ten’s office-based opioid treatment program, echoes Leavell. “The isolation, the increased depression and anxiety has led to increased use,” she says.

As a result, treatment and recovery services for people with substance use disorder remain vital. In March, C-VILLE covered how recovery groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, have transitioned online during the pandemic. Similarly, some treatment and recovery services for those with opioid use disorder have shifted online.

“It’s not the same level of support that you would have if somebody was coming into the office, honestly,” Leavell says of the virtual options. “And it makes things like urine drug screening more difficult, as well.”

But Leavell also says that telehealth services have made it possible to see new patients. This spring, enrollment in Addiction Allies’ intensive outpatient program has tripled. “Which I think speaks to both the increased stress and the increased use [of substances] during this time, but also the importance of the telehealth service delivery in order to reach people who are having transportation issues [and] childcare issues,” she says. “Everything is easier if you can access treatment from your home.”

The OBOT program has retained almost all the individuals under its care during the pandemic, says Fitzgerald. A central component of the program is medication-assisted treatment, where drugs such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone may be used to reduce dependency.

This medication-assisted treatment can be done via telehealth, Fitzgerald says, and prescriptions are sent to the patient’s pharmacy of choice or delivered by Region Ten if necessary.

Leavell says that medication-assisted treatment through telehealth, though not ideal, is safe. “When we’re talking about opioid use disorder, it is a very, very uncomfortable withdrawal,” she says. “However, it is unlikely to be lethal and the transition from using opioids to moving into medication-assisted treatment, such as the use of buprenorphine is typically fairly smooth.”

Other services combating the opioid crisis have also been impacted by the pandemic, and Region Ten offers free opioid reversal training classes, which have been moved online, and participants now receive Narcan through the mail.

Leavell emphasizes that, given the emotional and financial strain of the pandemic, it’s especially important to be aware of the causes of opioid addiction. “There’s a misconception that addiction couldn’t happen to someone like me or my family. And the reality is that it can absolutely affect anyone. It is just a matter of being prescribed an opioid and becoming physically dependent,” she says. “And if we’ve been fortunate enough not to experience that, I think we have responsibility to help those who have through no fault of their own, through making those resources accessible and being willing to talk about it.”

Correction, 8/19/20: Virginia Leavell is the chief of CARS, not the president, and buprenorphine, not Narcan, is used for medication-assisted treatment.