From the seventh-floor balcony of the CODE Building, downtown Charlottesville stretches out in front of you, misty blue mountains visible in the distance. Up here, North Downtown’s brick buildings, with their shingled roofs and quaint steeples, look like Monopoly pieces. And the seventh floor isn’t even the top of the office tower—two more floors of shimmering windows and black concrete rise above.

After years of construction, the place is just about open for business. Tenants are arranging their desk chairs, and the lobby’s coffee shop—Millisecond, an offshoot of Milli Coffee Roasters—is pouring joe as of this week. The caramel-hued foyer looks like the lobby of a high-end boutique hotel, with Bauhaus-style lamps hanging over leather couches. Before long, anywhere from 400 to 600 finance and tech workers will move in.

“The idea is that you have food, and sources of good energy, in the courtyard and also interior to the space,” says Rob Archer, who’s in charge of the co-working area on the building’s two bottom floors. The building itself—the Center of Developing Entrepreneurs, CODE for short—is the brainchild of mega-rich hedge fund manager and UVA alum Jaffray Woodriff. (The building’s general manager, Bill Chapman, is a co-owner of this paper.) The complex aims to “become the nexus of commercial and social enterprise activity in central Virginia,” according to the building’s website.

CODE sits at the end of the Downtown Mall, where the ice rink and Ante Room music venue used to be. The building’s floor plan is an irregular A-shape, drawn so that the tall office tower would be situated on Water Street. A triangular courtyard opens on to the mall. The architects went to great lengths to keep the original brick facade of the Carytown Tobacco building in place at the courtyard’s corner, though they painted the old bricks white with black trim, a sleek scheme to match the rest of the complex.

The new tech hub has aesthetic pedigree. Thomasin Foshay, who coordinated the building’s interior design, points out the courtyard fountain, designed by a member of the team that built the memorial at Ground Zero in New York; the rooftop garden terraces were installed with consultation from someone who designed the High Line in Manhattan. A dangling 21-foot interior sculpture, designed by an apprentice of Frank Gehry, lights up at night, offering passersby a glimpse of luminous floating polyhedrons through the window.

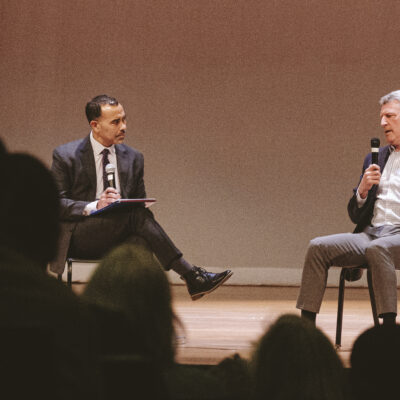

In the building’s red-carpeted, 200-seat theater, more bells and whistles become apparent. The chairs are “slim profile jump seats,” says Foshay. At first glance, each seat looks impossibly thin, but unfolds to create a two-part chair. When it’s time to divide the theater from the entryway, a partition appears from behind a hidden panel in the wooden-slatted wall.

“This is an amenity for tenants, co-working members, and also the community,” Archer says of the theater. The next event on the calendar is a holiday party for CAV Angels, a UVA alumni group of angel investors.

The building’s first two levels are dedicated to Codebase, the open-concept office space that allows members to buy access at a variety of tiers. At midday on a Monday, three or four people with computers sit here and there, plugging away. “What we’ve seen so far is that people are here, and they’re being extremely productive,” says Archer, a tech entrepreneur, UVA lecturer, and owner of Arch’s Frozen Yogurt. “That’s the whole point.”

A single individual can fork over $250 a month for 9 to 5 access to the office space, plus amenities like a kitchen, showers and a podcast studio. A four-person private office—with floor-to-ceiling windows looking out towards the Omni—goes for around $2,500. Twenty of the 38 offices are leased so far, and the co-working space could ultimately support as many as 200 people.

“In this space in particular, the pandemic has actually been an accelerator,” says Archer, citing companies’ desire for flexibility. The minimum membership period is two months.

Meeting spaces of various sizes are accessible from the co-working floor. “We call this a huddle room,” Archer says, opening the door to a green-walled space with a table and chairs. “But it’s really a conference room.”

Besides the lingo, other little hints of the entrepreneurial spirit are everywhere. In one conference room, ornate black and gold wallpaper shows vines curling around coffee cups and cell phones. One early tenant has hung a portrait of HGTV’s Property Brothers on their glass-walled office. Even the mailboxes have a touchscreen—you’ll need a QR code emailed to you to get your packages.

The building was designed to facilitate “collision,” says Andrew Boninti, a lead developer on the project. Central to that mission is the retail on the ground floor. Two restaurant spaces open into the courtyard: Ooey Gooey Crispy, which bills itself as a “grown-up grilled cheese” shop, is on the way, as is a storefront for organic Mexican fusion food truck Farmacy.

Will the restaurants be enough to draw passersby into the orbit of the looming building? “We like the concept that people understand that it is private property,” Boninti says, “that people are here on invitation. But that’s what we’re all about—collision of ideas. People running in to each other.”

The higher floors, four through nine, are designed as more standard office space for large companies. So far, three of the six floors are leased, with Woodriff’s firm, Quantitative Investment Management, taking floor four. Investure, a local financial planning and investment company, is fully moved in to floor five. Floors six through eight remain unclaimed, though Boninti says at least one more deal is imminent.

The pandemic has made large tenants a little hesitant to jump in. “They don’t know what they’re coming back to,” he says. “‘Are we gonna do three days a week at home?’ and all of that. I would think before the pandemic we would have had all of the spaces taken.”

Down at the bottom of the building, in the underground parking lot, 10 glowing green electric car chargers hang in front of the rows of spaces. (None of the 15 or so cars parked at the moment are plugged in.) Other environmentally conscious features include a rainwater collection system that catches water and pumps it back to the plants on the terraces. An elaborate air filtration network ensures that fresh air is always being blown in to every space—an expensive feature, but one Woodriff insisted on, citing research that fresh air boosts cognitive function.

Initially, Woodriff didn’t want to install a parking lot at all, says Boninti—“He thinks the future is going to be less cars, public transportation, and Ubers and everything else”—but the building has room for 74 cars, enough for the tenants’ bigwigs. “We have secured a lot of off-site parking,” says Boninti. “We have 100 spots at the Water Street garage, we have spots at the Omni, we have spots across the street at Staples.”

Most people, however, will encounter the building on foot, as they stroll down the mall. Amid two-story, red-brick storefronts filled with boutiques, restaurants, and used bookstores, the shiny, black, angular CODE building sticks out.

When Archer learns that C-VILLE asked about the building in its question of the week (p. 33), and one of the respondents said it reminded them of the Death Star, he says: “How do you respond to that? You don’t. You just say ‘hey, you’re entitled to your opinion. We love you, come check us out if you get a chance, the coffee’s good.’”