Deirdre Gilmore has watched her grandson become a statistic. The 17-year-old was originally arrested for truancy and has been in and out of juvenile detention for two years for probation violations, and Gilmore fears that she may “lose him to the system”—in part because of his race. “I don’t think he would be locked up if he was white,” she said.

|

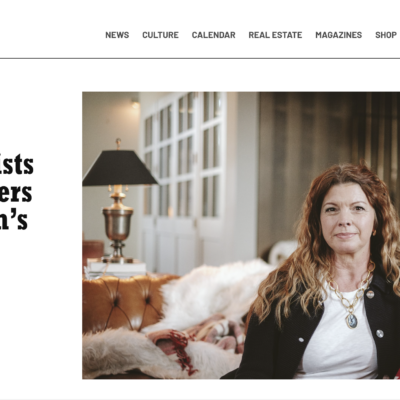

Deirdre Gilmore, a Charlottesville public housing resident, fears that her incarcerated grandson has been lost to the system. She strives to provide opportunities to minority youth, but said she can’t do it alone. (Photo by John Robinson) |

Gilmore, an employee of the Public Housing Association of Residents, is not the only one concerned about racial inequities in the juvenile justice system. In 2009, the Charlottesville/Albemarle Commission on Children and Families appointed a task force to investigate racial disparities across the board, and researchers recently presented their definitive findings to City Council: Black youth are disproportionately represented in the juvenile justice system. And locals are not letting that fact fall off the city’s radar.

The report reveals that in Charlottesville, black children are one-and-a-half times more likely to be put on probation or sent to detention, and white youth are four times more likely to be diverted from the juvenile justice system once they enter.

Gilmore spoke at the April 16 Council meeting, sharing her grandson’s story and begging the city to take action.

Her grandson’s original offense was minor, Gilmore said, but probation violations kept him stuck in the system, and the report shows that black youth are almost twice as likely to be put on probation as white youth.

According to Todd Warner, a graduate student studying psychology at UVA who participated in the research, the juveniles in the study did not differ significantly from one another on key risk factors.

“These are kids that are already brought into the juvenile justice system,” Warner explained.

He said they did not have access to numbers regarding at-risk kids as a whole, only those who entered the system. “But of the kids that are brought in, we can see that they’re showing similar patterns of risk, and the black kids are penetrating the system further,” he said. The term experts give this problem—of non-whites facing a higher likelihood of involvement in the justice system—is disparate minority contact, and the study shows it’s a reality for Charlottesville youth.

City Councilor Dave Norris said he was “very troubled” by these racial disparities, and the city is using an existing criminal justice committee to collect and examine more information. At the same time, the city is establishing its Human Rights Task Foce to collect data on discrimination. The task force was a key recommendation of the Dialogue on Race, but several Dialogue members quit earlier this year after the city balked at making the task force an investigative authority with enforcement powers.

“We’re working to get to the heart of it and figure out how to make sure that the justice system is colorblind,” said Norris.

Warner said the task force recommended more data be collected earlier down the pipeline to determine what decisions were being made before and after arrests.

Charlottesville Police Chief Tim Longo said his department is in the process of implementing a new system to collect data on field stops to determine the race and age of those stopped, and why the police pulled them over. He said the department has not yet determined what specific form will be used, but officers will be able to file some sort of report that will determine the incident type.

According to Longo, the department’s current data system makes it virtually impossible to look at an initial police contact and follow the case all the way through to a final disposition in courts.

“That’s somewhat of a barrier when it comes to looking at statistical information and drawing conclusions from it,” he said. He agrees that the disproportionate minority contact is a problem, but said even with the data, the question of why it’s happening remains.

Jeff Fogel, a local attorney who has long been vocal about civil rights issues, said the problem is poverty. He said officers are more likely to frequent densely populated areas, and objective stereotyping leads to subjective decision-making.

Gilmore agreed. “They come into our neighborhood for the numbers,” she said, and she is not surprised by the results of the study.

“I think there’s a lot of harassment going on,” she said, and she feels that, instead of providing protection, police try to instill fear in minority youth.

When Gilmore is not working at PHAR, she is reaching out to youth with engaging neighborhood activities.

“You have to have programs and you have to have mentors that care about them,” she said.

Gilmore said that once a child is in the system, he or she needs access to rehabilitative services and better re-entry planning. She said her grandson needs therapy for substance abuse, but the service has not been offered since his incarceration, and Gilmore fears he will return to his old habits if he does not get the help he needs.

“We’re all in danger because of the way the criminal justice system works,” Fogel said. “The criminal justice system is creating crime.”

He and Gilmore agree that the system focuses too heavily on punishment, with too little emphasis on rehabilitation.

“If you’re going to incarcerate our kids,” Gilmore said, “at least give them help.”

/DeirdreGilmore.jpg)