More than two hundred years after she departed North Dakota as a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Sacagawea of the Shoshone tribe is at the center of controversy in Charlottesville—again.

At issue is her depiction in a statue on West Main, where she crouches at the feet of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. The statue, gifted to the city by local benefactor Paul Goodloe McIntire (who also commissioned the Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson statues), has been a target of protests for years.

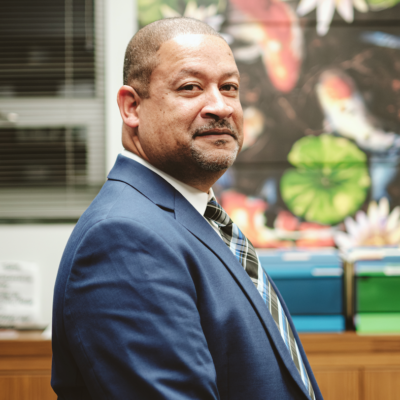

“It still is probably the worst statue of Sacagawea in the country,” Anthony Guy Lopez, a UVA alumnus (’09) and member of the Crow Creek Sioux tribe, said at a June 17 City Council meeting. “If you do the research, you won’t find another one as demeaning.”

It was renowned sculptor Charles Keck’s idea to add Sacagawea to a statue that was originally intended to depict only Lewis and Clark. Her inclusion may have been considered ahead of its time back in 1919, but more recently, critics have objected to her subservient posture in relation to the explorers (others say she’s tracking or foraging for food).

The issue was back in conversation because of the West Main Street improvement plan, a $31 million project which requires that the statue be moved 20 feet. Some suggested the city take the opportunity to relocate the statue altogether. But, as often is the case in Charlottesville, councilors say more feedback is needed.

After initially approving $75,000 to form a committee to decide the statue’s fate, City Council decided instead to seek the input of Native Americans in a work session, using some of those approved funds to cover the invitees’ travel expenses. Councilors hope to include descendants of Sacagawea and Councilor Kathy Galvin also proposed inviting the recently appointed U.S. poet laureate, Joy Harjo, who’s a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation.

“I see this as a great opportunity to gain more insight and wisdom about the Native American community’s perceptions of this statue and then we as duly elected representatives of this community have to take in all that information and make a decision on whether the statue stays or goes or whether we add context,” Galvin says.

One potential landing spot for the statue is the Lewis & Clark Exploratory Center in Darden Towe Park. Executive Director Alexandria Searls has invited City Council to consider moving the statue to the facility’s front lawn, where it can be viewed more easily and contextualized to explain how Sacagawea’s crouched position recognizes her skills as a tracker and forager.

“It used to be [in] a big park called Midway Park, where you could really get close to the statue and see the details on the side,” Searls says. “As that park land became what it is today, which is basically next to nothing, it’s changed the way we encounter that work of art.”

Searls insists she isn’t lobbying for City Council to move the statue in front of the center, but rather providing it as an option for the councilors to consider. The center, a nonprofit, doesn’t have the resources to fund the statue’s upkeep, so the city would still have to pay for its removal and maintenance, says Searls. However, Searls says donating it would align with the city’s desire for the center to be a tourist destination, as the statue figures to be a significant draw for visitors.

It’s impossible to tell the story of Lewis and Clark’s trek across the continent without talking about their navigator, translator, forager, and tracker.

Even though she was only a teenager, Sacagawea played an integral role on that historic journey. Her knowledge of the Hidatsa and Shoshone languages was pivotal, and she proved invaluable with her ability to collect food and medicinal herbs.

But this isn’t the first time residents have raised issues with the statue. In 2007, local performance artist Jennifer Hoyt Tidwell organized a demonstration on Columbus Day. She collected 500 signatures protesting Sacagawea’s portrayal, prompting the addition of a plaque commemorating her contributions that was installed two years later. Mayor Nikuyah Walker pitched the idea of moving the statue last November.

For now, City Council has already voted to go ahead with moving the statue 20 feet as part of the West Main Street improvement plan. That project, which has been in development since 2013, aims to ease traffic congestion, expand surrounding sidewalks, plant more trees, remove overhead wires, and replace underground gas lines. According to Galvin, construction is expected to begin in “about a year.”

A timeline hasn’t been established for the work session or an eventual decision on the future of the statue. To prevent anyone from feeling alienated by the decision, Galvin says “it has to take as long as it has to take” for all parties to have the chance to give their input.

“The removal and the relocation of the statue is not the most important thing,” Lopez says. “The most important thing is that … a good, healthy relationship can be established between the city and Indian country.”

Correction (6/27/2019, 9:00 a.m.): A previous version of this story stated Sacagawea departed from St. Louis for the expedition. Lewis and Clark did begin their journey in Missouri, but didn’t encounter Sacagawea until they arrived in North Dakota.