By Caroline Challe

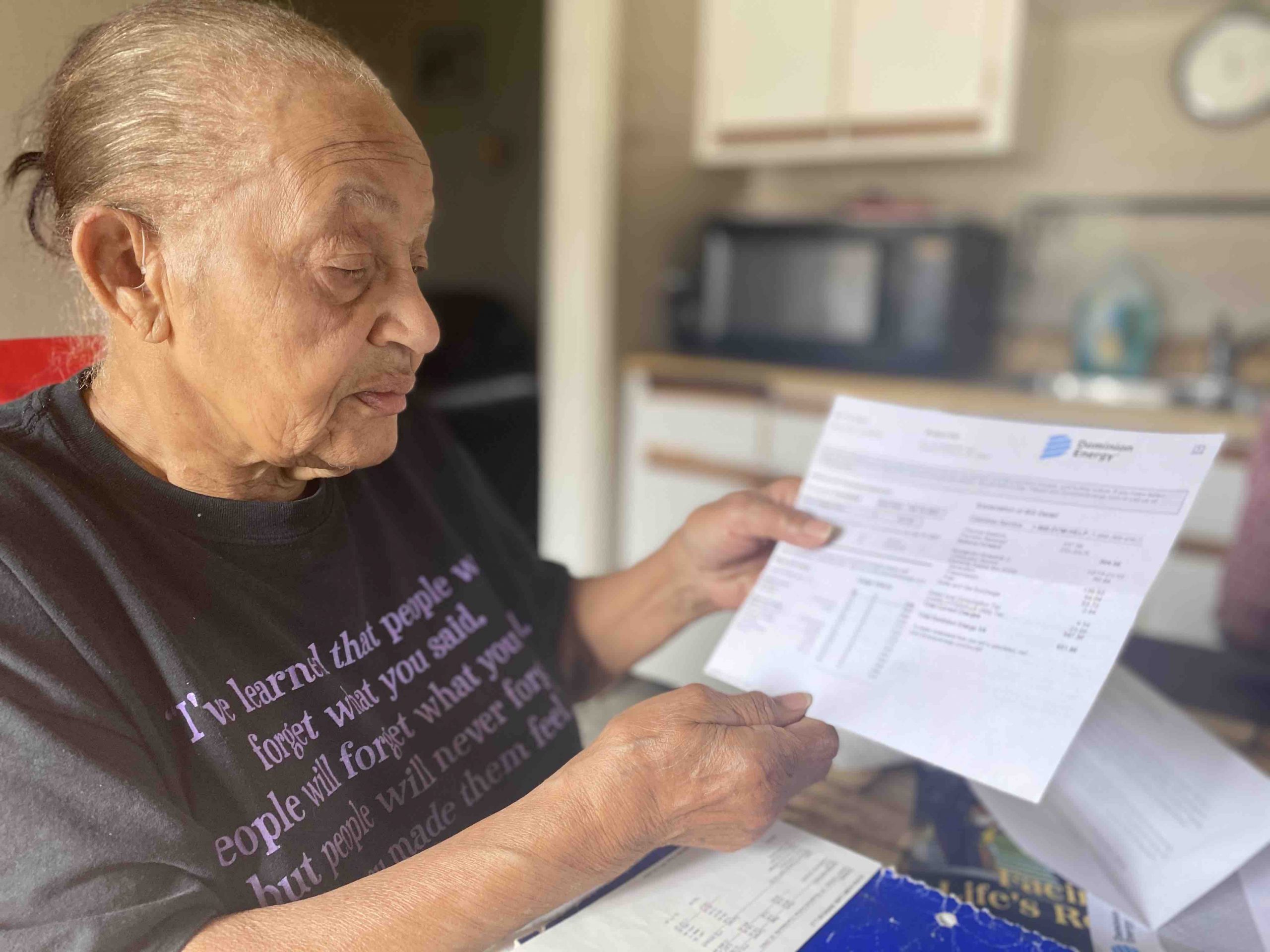

For Carolyn Johnson, a Charlottesville homeowner and care worker, the financial strain of the pandemic has been exacerbated by her high energy bill—almost $300 last month.

“Water bill and electric–them the highest thing I got. It’s really hard. I am struggling trying to get it done,” Johnson says. Though her household’s energy habits are typical, Johnson says, “by the time we pay up everything, we end up with maybe $200 left.”

Johnson is one of the three-quarters of Virginians who have an unaffordable energy bill according to federal standards, says Cassady Craighill of the climate advocacy organization Clean Virginia.

“We have a real crisis in Virginia where our energy bills are too high. They’re the sixth highest in the country,” Craighill says.

The prices are all the more galling given that Dominion, Virginia’s energy monopoly, has an enormous cash stockpile. Dominion has near-total control over swathes of the Virginia energy market. In exchange for that power, its profits are traditionally limited to a rate agreed upon with the state—in recent years, 10 percent. Profits above that threshold are supposed to be refunded to customers.

In the last three years, however, Dominion pocketed $500 million more than that rate of return, because a 2018 law allows it to keep excess profits as long as it invests the profits in clean energy projects.

Delegate Sally Hudson believes that over-earnings leave Virginia residents economically vulnerable.

“I’ve met lots of constituents struggling to make ends meet, and between sky-high rent and utilities, just affording safe shelter is a major struggle,” say Hudson, who represents Charlottesville and part of Albemarle County. “The burden of electric bills also hits hardest for the families that already struggle most, because they typically live in units without the more modern energy efficiency measures like improved windows, insulation, and thermostats.”

Despite the astronomical over-earnings, Dominion claims that its rates are low, and consumer error is the reason many are facing astronomically high prices.

“Hopefully, people you know, set their thermostat at the right temperature so that they’re not driving those bills up,” said Rayhan Daudani, Dominion’s manager of media relations.

Daudani says the company’s re-investment of the over-earnings winds up benefiting customers. “Instead of charging customers the costs of the projects, we would take the extra revenue and offset those costs, so that they get the benefit of the project without seeing any rate increase.”

I’ve met lots of constituents struggling to make ends meet, and between sky-high rent and utilities, just affording safe shelter is a major struggle.

Delegate Sally Hudson

Dominion opponents have concerns about those clean energy projects, however. One of Dominion Energy’s newest projects involves building wind turbines off the coast of Virginia Beach. The company says the project requires large over-earnings in order to produce this expensive form of clean energy.

“Dominion receives a 10 percent annual rate of return on anything that they’re building. So instead of cost-efficient renewable energy like rooftop solar that is distributed all over Virginia, they’re going to choose to build a much more expensive renewable energy project so that they can get that rate of return as high as possible,” says Craighill. “And that’s how a monopoly works.”

As the pandemic rages on and millions of citizens struggle, a bill was proposed that would have required the State Corporation Commission to return 100 percent of the amount of a utility’s earnings back to customers’ bills. On February 1, that bill was killed by the Virginia Senate Commerce and Labor committee. In an 11-3 vote, the bill was “passed by indefinitely,” effectively terminating its chances. Eight Democrats and three Republicans decided to tank the bill, while three other Democrats voted in favor of it.

When the bill failed, many advocacy groups like Clean Virginia cited Dominion’s hefty donations to state officials as the reason why. Dominion has long been the largest contributor of campaign funds to both political parties in the state, although recently some Democrats have sworn off its contributions.

“When you have a company like Dominion giving those same legislatures hundreds of thousands of dollars every year, that’s a huge conflict of interest since clearly, those legislators are going to have a hard time convincing their voters and constituents that they’re acting in the best interest of them when they’re routinely passing legislation that favors Dominion,” says Craighill.

Hudson, who works with many legislators who have accepted Dominion’s donations, believes the company uses its capital to maintain influence over the General Assembly.

“The state guarantees that Dominion will recover its costs for those projects anyway. The company doesn’t need to over-earn to make clean energy investments,” Hudson says. “Dominion writes its own rules, and some legislators just sign off. They don’t want you to understand why you’re not getting a fair deal. Fortunately, there are fewer and fewer of those legislators every year.”