|

Only days before her students take one of those major state Standards of Learning tests known in Virginia as SOLs, Charlottesville High School biology teacher Lori Mack isn’t getting the message across to her second period class of ninth graders.

“It doesn’t matter if I pass this test or not, because I’m still going to be a 10th grader,” says a student, reflecting years of conditioning from so-called social promotion.

“Anybody see the yearbook?” replies Mack, a 20-year veteran always looking for a teaching moment—those times when a seeming tangent is turned into an unexpected lesson. Mack points out the 18-year-olds still listed in the freshman class.

The girls start paying attention: Who wants to be stuck in ninth grade?

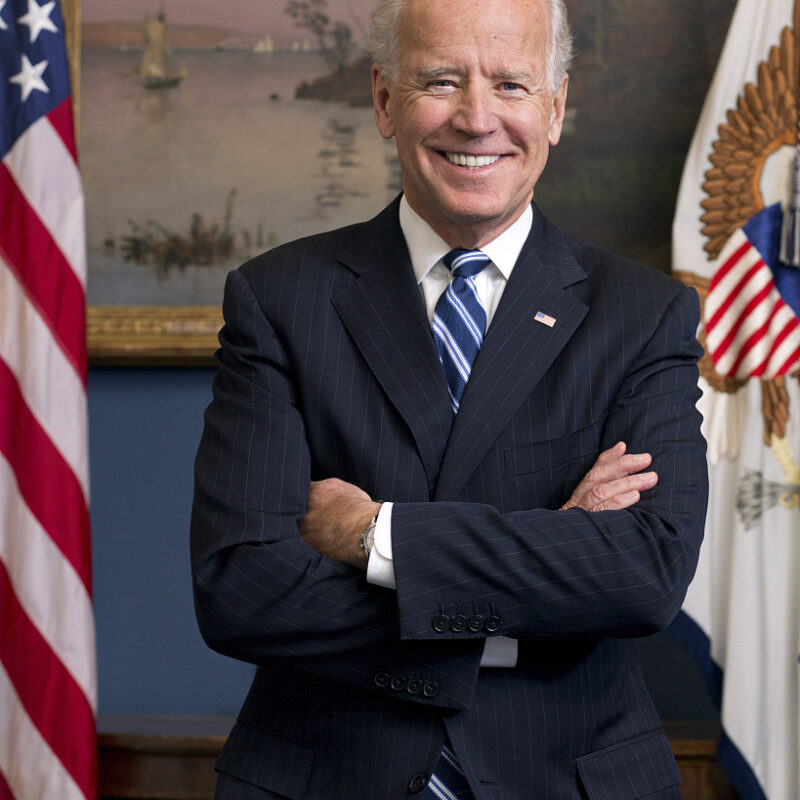

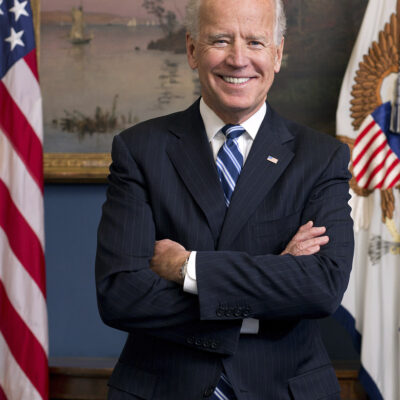

Lori Mack, biology |

Kim Thompson, algebra |

At the John Paul Jones Arena on June 5, 261 students walked across a platform and were handed diplomas. Friends and family speckled the seats in the cavernous facility to cheer on the graduates, to snap pictures of their babies in blue gowns, to celebrate their child’s achievement—getting past the first major boundary line of the educational system.

Chad Prather, world history |

Josh Walton, English |

Taking up less than half of the floor of the JPJ, the Charlottesville High School graduating class of 2007 looked small. And it was small, compared to the 451 students in ninth grade four years ago at CHS. Each year since, the class size has dwindled—369 in 10th grade, 309 in 11th grade.

What happened to those other 190 kids from ninth grade? Some, no doubt, transferred to other schools, and some got high school equivalency diplomas, and some are a year or two away from graduation. But many of those kids are now working low-wage jobs or languishing in the court system or looking after children of their own.

I’ve never met a ninth grader who says, “I want to be a high school dropout.” For three years, I taught theater arts to ninth graders in a struggling school in eastern North Carolina’s Halifax County, where 95 percent of students were minorities and over 50 percent received free or reduced lunch (meaning they’re within 185 percent of the poverty line, $20,650 for a family of four). I had ninth graders who turned in zero homework assignments, rarely performed an assigned scene and missed 20 days of class. But those students, who seemed on a mission to fail my class, never said they wanted to drop out.

Yet students do drop out of the educational system, at Charlottesville High, in Albemarle County, and all across the country. Last year, 58 students dropped out of CHS, and those are only the official dropouts [see sidebar, right].

Now that they’ve dropped out, no one needs to tell them the stats on the “high school dropout” category to which they now belong: that they earn on average $9,200 less per year than high school grads, are twice as likely to slip into poverty, are eight times more likely to be in jail.

A recent study by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation found that 70 percent of dropouts surveyed were confident they could have graduated from high school, that 88 percent had passing grades. But somehow something somewhere caught up to them. And much of the time, that something is in ninth grade.

Research shows that ninth grade is a make or break year: If a child is held back, the likelihood he or she doesn’t graduate shoots up dramatically. At CHS in 2005, 25 percent of all ninth graders were retained.

Why such a large failure rate? Ninth grade presents one of the biggest transitions in the educational ladder: Students are moving to a new school, going from being a big fish to a little fish; they are being ravaged by the ups and downs of puberty; and they’re adjusting to an academic environment that is sink-or-swim compared to middle school.

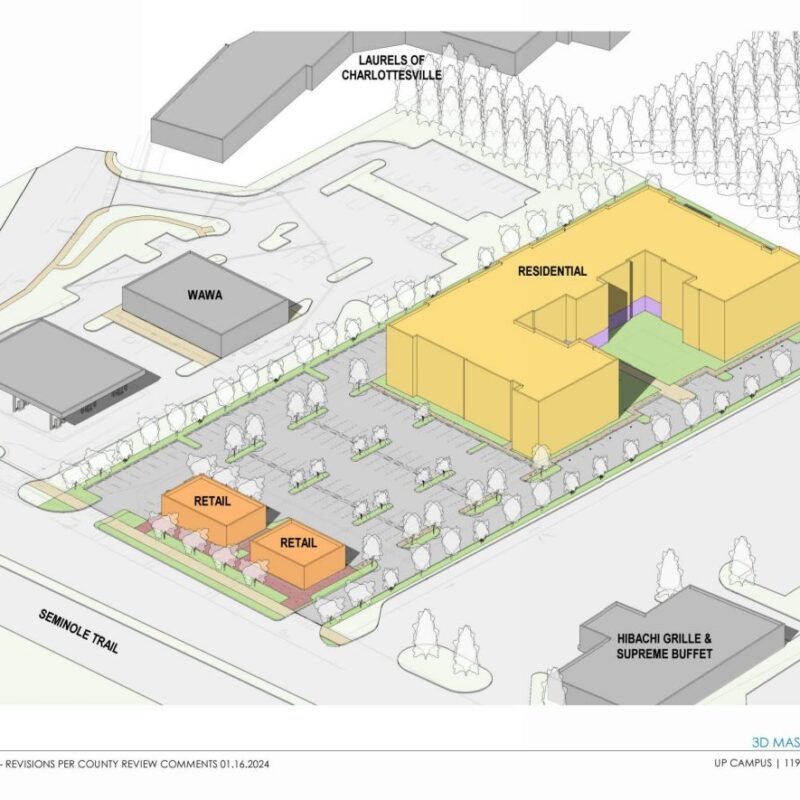

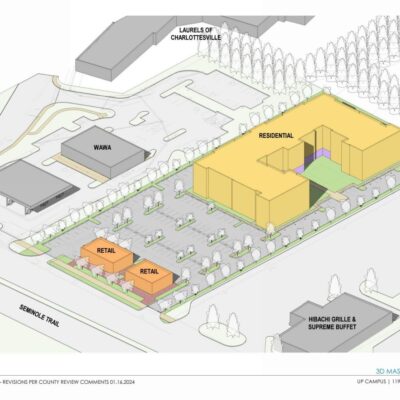

For the past four years, a group of dedicated teachers at Charlottesville High School—Carly Borton, Lori Mack, Chad Prather, Kim Thompson and Josh Walton—have been working hard to ease that transition for students most at-risk to fail ninth grade, and drop out down the line.

“The kids who don’t want to be taught”

Each fall, about 80 freshmen at CHS learn that their school days aren’t quite like others. All of their academic classes are in the morning. All the classrooms are close together. And all those classes are spent with the same classmates.

They soon learn other things: When they don’t turn in an assignment, the teacher notices—and gives them hell for it. When their parents come in for conferences, all their teachers show up. If they need extra help but don’t show up for tutorials, Mr. Walton can issue an overnight suspension, meaning that the next day, a parent or guardian must come back with them. They learn that Ms. Mack will listen to their problems—even if they aren’t about biology—and that her door is open for lunch. When they have a bad day in Mr. Prather’s first period, Ms. Thompson seems to know about it without a word.

The Freshman Academy, originally called Block Nine, was implemented in the 1990s. CHS has four levels of classes: honors, advanced, general and standard, standard usually reserved for the learning deficient. Freshman Academy is geared toward kids taking general level classes—kids who typically haven’t been celebrated by the school, to use the words of Prather, a world history teacher.

“As a result, by the time they get to the high school, some of them have checked out motivationally,” Prather says, “and don’t look at their education in an academic way, look at it in more of a social way.”

When it started, the program significantly reduced ninth grade failure rates, says Bobby Thompson, who was then CHS principal. But it went through its ups and downs until a core group of teachers were thrown together and started to click.

What has made Freshman Academy significantly more successful is that a core group of teachers have stuck together for several years to make the system work. What’s helped is that the administration has stuck with the program and supported the Academy teachers.

Making any big-idea program work has as much to do with implementation as it does with concept. And implementing a new idea—implementing it so that it stays in place—is the hardest part. In Halifax County, I watched a giddy assistant principal, flush with grant money, return from a conference and immediately try to set in place a schoolwide version of Freshman Academy. She scheduled ninth grade classes in the same hall. She passed out instruction manuals to every ninth grade teacher and booklets to every ninth grade student, and had us all sit through hours of explanation about how great it all would be, how ninth graders wouldn’t fail as much and would be more focused.

But the principal got tied up in the daily grind, and six weeks into the school year, I heard nothing more about the Freshman Academy. I never had any common planning-period meetings with other freshman teachers, no heart-to-hearts about Jeremy’s anger or Dorey’s work ethic. All the notebooks and enthusiasm were meaningless unless someone forced it all to come true.

Yet somehow that happened at CHS. For four years, a core of teachers has kept working at their new system, doggedly pursuing an idea of making it better.

On paper, they don’t have much in common: Walton and Prather are young white men with degrees from fancy Virginia universities; Kim Thompson is a black woman who grew up in Fifeville and is now on her third career; Mack is a 20-year veteran teacher who loved teaching middle school; Carly Borton, an algebra teacher on maternity leave during my observations and interviews, is a young woman from Oregon.

Their teaching styles are as different as their backgrounds. Prather, who teaches world history, tends toward the academic. He spends hours on his lesson plans, and has presented at a national conference on differentiation—tweaking lessons and assignments to fit the different interests, learning styles and skill sets of the students in a class. Walton, an English teacher, has been drawn toward administration and serves as coordinator for the group. Kim Thompson has a tough-love veneer, betraying her pleasure when helping guide students through the rigors of first-year algebra.

And then there’s Mack. She doesn’t just teach—she performs, mugging for students, sharing stories of students past, catching quieter kids off guard by noticing what they’re up to. She’s full of phrases like, “You get nothing but nothing for nothing,” and her cluttered but organized biology classroom has postings like “The best things in life aren’t things” and “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” She’s unabashed to lay calming ha

nds on hyper students and between testing tips and a study review, takes three transitional minutes to read her students’ horoscopes from The Daily Progress (with her own twists thrown in): “You can do whatever you like today—but not in biology class. If you step over a line or break limits, you will face trouble—in biology class.”

“It became clear to me after eight years of teaching—and I took heat from administrators and other teachers—that I couldn’t be an effective instructor unless I had a relationship with my students,” says Mack. “It doesn’t matter how many hours I put into a lesson plan if there isn’t an established relationship there with this core of kids. The translation is lost.” Of the nine students I interview, all mention Mack in some way or another—even if playfully chagrined that she “picks on me.”

Somehow, this diverse team stayed together for four years (with the exception of Thompson, who joined them three years ago). “We have very different styles of teaching, but we share a common philosophy in that we teach children first and our content second,” says Mack. She describes Freshman Academy as the pinnacle of her team teaching experience. “I don’t know that I can get any better than this.”

Each year, the teachers have altered systems to help fix their most urgent issues with students. Kids don’t turn in work? Not enough time in the day to catch students up on assignments? Create an after school tutorial program. Students who need the tutorial not showing up? Make it mandatory for certain students. Students still not showing up? Tweak the discipline system so that they have to show up with a parent the next day if they miss tutorial.

Of course, those changes often involve more work. “Every year we seem to get more and more frustrated at different times, wondering if things are going down hill,” says Prather, who, until he was married this year, would regularly be at school from 8am to 9pm. “But if there were a motto for Freshman Academy, I think it would be: The job we do doesn’t get any easier if we’re any good at it. Every year we find something that irks us so much we have to change it.” Yet Prather and Thompson and Walton and Mack have kept coming back for more. “We come back because we want to teach the kids who don’t want to be taught,” Prather says.

This year, they established a program with UVA’s Office of African American Affairs, bringing their ninth graders out for workshops with UVA students. Some of those college students shared their stories of turning around subpar high school careers, while some cajoled the ninth graders to raise their standards. For many of the students, it was their first visit to UVA.

“We really want them to see [college] as something that’s very much attainable—with the right mentorship and inspiration, you too can come here,” says Dion W. Lewis, an assistant dean for the Office of African American Affairs who ran the program.

During the fall semester, the team of teachers meet formally twice a week to discuss anything from individual students to the upcoming Teens GIVE field trip, where they take students out to volunteer in the community (one of the most cherished memories of Academy alums). And then they meet informally almost every day. “I can walk into four different classrooms outside my own at any time of day and with a single glance, another teacher will know exactly what I’ve been through,” Prather explains. It gives them an opportunity to vent—to share the myriad frustrations that come from teaching students who only come to school to socialize. Students who are the opposite of what these teachers were as students themselves.

They can do that because their planning periods, the times they don’t have to teach, are scheduled at the same time. “There really is no substitute for having a group of teachers, all of whom work with the same students, meet together periodically and monitor the progress of those students,” says Daniel Duke, an education professor at UVA who has written extensively about ninth grade transitional programs. “That is the bottom line when it comes to raising performance. It all begins with teachers and their ability to understand which students are struggling and which students aren’t.”

The continuity over the years also means that when a student leaves ninth grade, he knows that when he’s having trouble in Algebra class, he can get help from Ms. Thompson. Or she can eat lunch with Ms. Mack. Or use Mr. Walton as a sounding board for what to do after graduating from high school.

Inequality in the land of Jefferson

Success with ninth graders is an elusive mark, subject to daily revisions of expectation. A kid who will do anything to learn in a one-on-one tutorial becomes a recalcitrant brat when put in position to perform for her peers. Students wearing clothes with the cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants are talking about blowjobs.

In a one-on-one setting, a ninth grader may show an eagerness to learn—to write fluid sentences, to simplify a fraction, to understand the basic causes of World War II—that pits your stomach into a well of sympathy. But put that kid in a classroom full of fellow ninth graders, not 15 minutes later she may be shellacked in layers of indifference impenetrable by even our inner-Jaime Escalantes. The epiphanies are matches struck unexpectedly in the dark, not blazing bonfires for the world to see.

On any given day, it is difficult to find the magic of the Freshman Academy. I observe classes on a Friday in the midst of the SOL exams, and first period is a group that Walton and the other teachers say has been one of their biggest challenges this year. In a class of 20, only Walton stands to say the pledge of allegiance. A lesson on Romeo and Juliet draws little attention. For the first 10 minutes of a group quiz, most students seem more concerned with clothes and gossip and picking on each other, though several diligently work through the events of Act I. Not until the final minutes do most try to answer the questions on the quiz. Beside me, a student sings “Knees and toes,” staring out and looking for someone to distract.

Part of what I’m seeing is the release of steam in the midst of high-pressure SOL testing, which gained new significance with the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act [see sidebar, page 26]. The act puts pressure on all schools, but especially on a system like Charlottesville, which has long done an excellent job at providing top-notch classes for Advanced Placement and the performing arts, but has struggled to improve the scores for the poor, the black, and the limited English students.

At CHS this year, 40 percent of white students took AP or Honors level courses—compared to only 5 percent of African-American students, and 3 percent of “disadvantaged” (read: poor) students. Of last year’s students in Freshman Academy, 77 percent were black and 81 percent received free or reduced lunch.

In 2004-05, 91 percent of white children passed English SOLs at CHS, while only 54 percent of black students did so. Of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, 51 percent passed, and of those with limited English, an abysmal 25 percent passed. While 40 percent of white students showed advanced proficiency, only 4 percent of African-American students did so. This is what’s often called the achievem

ent gap.

CHS’s test scores for 2005-06 improved significantly across all subjects and for most subgroups. Black students’ English pass rate jumped to 74 percent, and to 68 percent for poor students. Still, those scores are below state averages, particularly for black and poor students though also slightly for white children. And for all the hubris of Charlottesville—with the state’s premier university, a highly educated populous and its boutique shops and restaurants—those gaps are troubling reminders that the community is failing in many ways to raise the bottom rung. Perhaps it fits the complicated legacy of the slaveowner who decreed “all men are created equal.”

Has the Freshman Academy worked?

For the past two years, Freshman Academy attendance for black students has been up 2-3 percentage points over black ninth graders in the school as a whole, though Academy attendance is actually several points lower for the white students compared to the rest of white ninth graders and only marginally better than ninth grade attandance as a whole. Academy students on the median have jumped two grade levels in reading from fall to spring semesters.

“I’m convinced that a lot more kids have graduated in four years since it started,” says Bobby Thompson, who was principal when Block Nine was initiated and is now the city schools’ assistant superintendent for administration services.

Anne Gregory, a psychology professor at the Curry School, led a study of the Freshman Academy this year, trying to identify what helps in the ninth grade transition. Her team shared the results with the Freshman Academy teachers last week: While Gregory couldn’t show that Academy students had more academic-achievement growth than non-Academy students, they did find that students in Freshman Academy perceive a high level of care from their teachers. The team teaching appears to be one of program’s central strengths.

But for the most part, the evidence is anecdotal: The student who goes from the general classes of Freshman Academy to AP Government. The uninvolved kid who joins Student Council and the debate team. The unmotivated athlete who would hardly open a book who now receives an advanced studies diploma—“we’re talking about a kid who if you would have talked to his middle school teachers,” says Mack, “they would have bet their bottom dollar he wouldn’t make it through high school.

“They’re just so unfinished. They just need a finesse to them. It’s really nice to see the transition—it’s my two week vacation in the Cayman Islands, it’s my stock option.”

Most of the Freshman Academy ninth graders I talk to are blasé about the experience. “It’s just basically a regular old high school,” says Malinda Logan. Jessica Lamb says the Academy probably made high school less intimidating and helped keep her from failing, but adds, “It’s kind of annoying, because everything is close together and I want to walk around the school.”

Upperclassman have more perspective on the program. Rising 12th grader Lacorie Steppe says he made better grades in ninth than eighth thanks to Freshman Academy. “Really and truthfully, I think if all the teachers around in the whole building did the same thing [as Academy teachers], a whole lot of people would be more successful in Charlottesville than what it is now.”

Cody Dalton, who graduated with an advanced studies diploma and has a track scholarship to Bethune-Cookman College, says he would have been a worse student outside Freshman Academy. “They were pretty good teachers, stayed on you, helped you a lot, but I just wasn’t a student for them, I guess,” Dalton says. “I wasn’t focused enough. If I could go back and do it again, I’d be a way better student.”

Erica Chapman, who also graduated with an advanced studies diploma, says she could better focus on her work in ninth grade than in 10th grade. That a ninth-grade program might make it harder to go on to 10th grade is an unfortunate possibility. Says Professor Duke: “The risk is, whenever you do anything unorthodox and then expect students to reintegrate into the mainstream, there’s the potential to react negatively whenever they re-enter.”

Still, unlike the average teacher, Freshman Academy teachers can be friendly faces in later years. Unlike most of Chapman’s other teachers, “when I walk through the hallways, they all remember me and speak to me.” And often a program, no matter how well designed, comes down to the quality of the teacher behind it.

Graduating at the JPJ were 40 students taught by the Freshman Academy teachers, out of a group of 90 back in the fall of 2003. Eight others are still associated with CHS, 24 have moved away, five have been dropped from the rolls because they’ve missed 15 days of school, two are in GED programs. Ten have officially dropped out. Discounting for those who moved away, that puts the effective graduation rate at 61 percent.

Breaking up

The Freshman Academy teachers say this has been the team’s most consistent year across the board. But even great teams don’t stay together forever, and the Freshman Academy team is splitting up after their four-year run. Walton will be an assistant principal in Madison County and Mack is off to Thailand, where as a military child, she spent some years growing up.

Rather than replace them, CHS is looking to, in some ways, replicate the Freshman Academy model across the ninth grade. While plans are not firm, CHS is looking to set specific administrators for the ninth grade and is looking at academic teaming for ninth grade teachers. There’s talk of setting up a homeroom period, where teachers can check-in daily with students on schoolwork and plans —but which can also become a time-wasting holding tank if poorly implemented.

Whatever happens, “I just hope that the program and the plan is monitored and tweaked and continues to get better,” says Walton. “Otherwise, it’s going to be another initiative that was created in an educational system that had a lot of promise and is going to fall by the wayside because of a lack of supervision and a lack of monitoring. And that’s not a knock to our administration and our teachers—we are overwhelmed.”

“But we still have a responsibility to serve our clientele,” adds Mack.

At the beginning of the school year, when his students ask him why he’s a teacher, Walton tells them: “I’m selfish, because I want to see an educated, responsible populace. Some people could say that’s misanthropic. But I think it’s more hopeful than anything.”