| C-VILLE‘s coverage of the NGIC land deal:

Pantops land will remain in growth area |

Early this May, I got a call from local land baron Wendell Wood. He had just seen a piece of mine in that week’s C-VILLE. It concerned a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request I had filed earlier in the year. I want to find out the amount of an undisclosed land appraisal performed on 46.7 acres he sold to the Army for a new (as yet unbuilt) intelligence facility next to the current National Ground Intelligence Center (NGIC). Would I come visit him at his office, Wood wanted to know. A week later, I sat in the offices of United Land Corporation with the developer at a conference table covered with maps and folders.

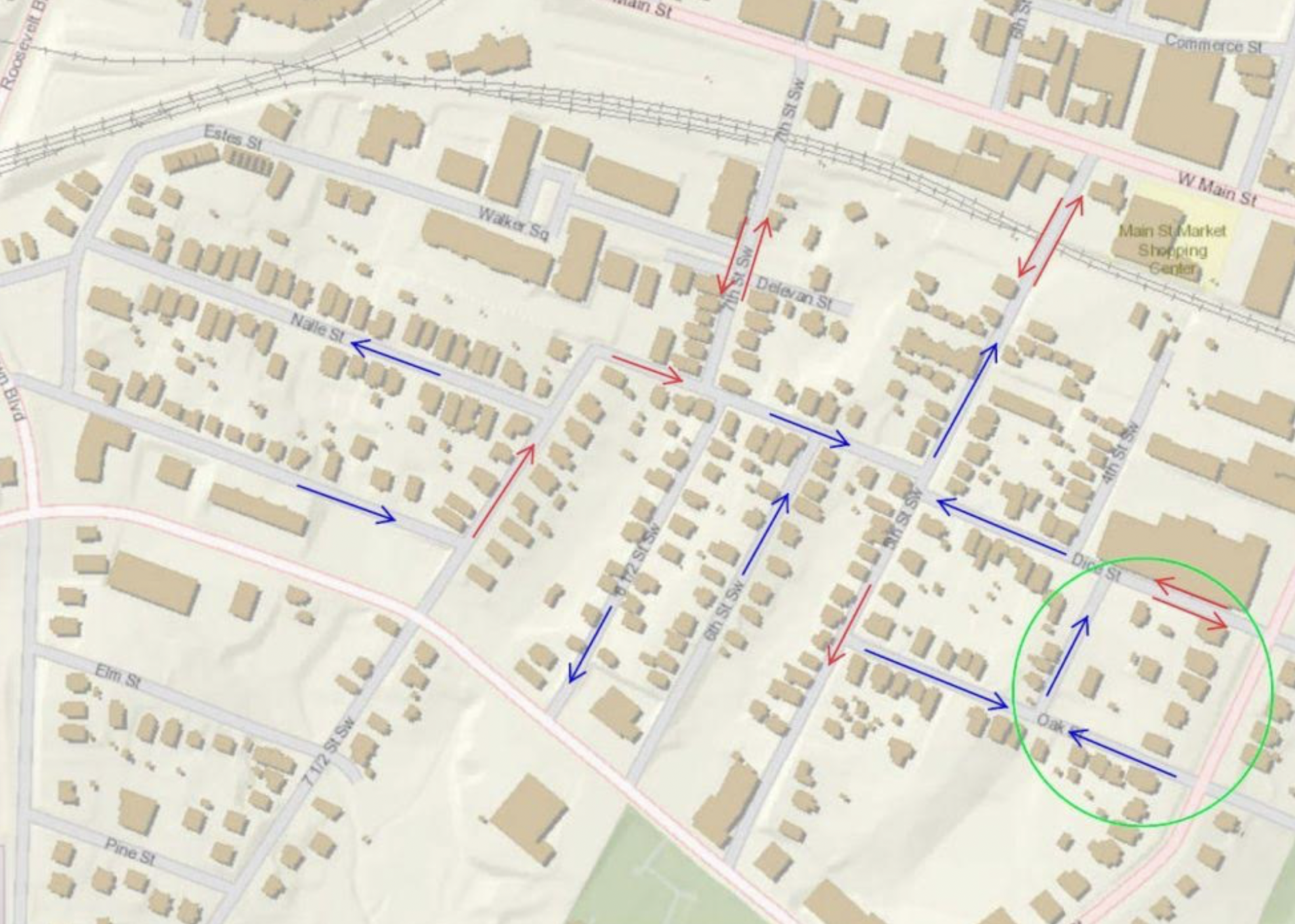

The short article he took objection to was a follow-up to a much larger C-VILLE feature that had pulled back the cover on a “resolution of intent” passed in May 2006 by the county Board of Supervisors. They had resolved to move 30 acres of Wood’s land around Route 29N into the Development Area in exchange for him supposedly receiving less than market value from the Army for the 46.7-acre parcel. It was an unusual move, as the boundary lines for the growth areas are rarely shifted (only one other time in the last 15 years, for the Crozet Master Plan) and when they are it is usually through a long planning process. In this case, the resolution was largely in secret and pre-empted the planning process—which has still not been undertaken, and will involve hearings at both the Planning Commission and the Board of Supervisors.

Sitting with me at the table, Wood explained that he felt my version of events cast unnecessary aspersions on the appraisal and the land deal. There was nothing nefarious about it, he argued, and to prove his case he pulled out a file folder and opened it.

Wendell Wood sold 47 acres to the Army for less than he claims it was worth, but he wants the county to share some of the burden and move 30 acres of Wood’s land into the development area. |

Inside were various contracts he had either recently completed or was still negotiating. For instance, the developer recently sold five acres by the airport for $2.5 million to the Church of Latter Day Saints of Waynesboro for a new sanctuary. As Wood folded piece of paper over piece of paper, I gathered that the average price he sells an acre for is roughly $500,000. If that’s the case, then Wood certainly took a hit on last year’s sale of 46.7 acres to the Army for only $7 million.

Overwhelming me with these numbers, he then suggested that maybe I was working on behalf of Sally Thomas, the only supervisor to vote against the May 2006 resolution. I assured him I was not.

Then he took issue with something I put in my original feature, that Bob Canar, the then NGIC chief of staff, had revealed the appraisal value to him. “I never said that,” he said. I distinctly remember him telling me so, and had immediately incorporated it into my research. If Canar did reveal the appraisal amount to Wood then Canar would seem to have violated a law or two, disclosing private information about the U.S. government’s activities to a private citizen. I wondered, was Wood covering for him?

Although in his 70s, Wood is still lively, especially so when talking about his land, and as he continued to expound on the benefits of having the intelligence facilities in our community, he also revealed some of his rationale behind development. Wood bought his first land in the early 1960s and has accumulated most of the land on both sides of 29N since. In the early ‘80s, he sold some to General Electric for $10,000 an acre. “I would have given it to them for free,” he said. Wood saw the GE deal as more important because it spurred the development of the 29N corridor. With land all around, Wood stood to benefit from the aftereffects of any development.

Twenty-five years later, Wood has changed his approach. Not only is he not willing to give land away, he wants as much as he can get for it, even if it means refusing to sell to someone like the Army, an entity he repeatedly holds out as the model of what Albemarle needs as far as jobs go. “We can’t all be flipping burgers for each other,” he has said over and over again, “or working at Wal-Mart.” Regardless of the perceived value, Wood vowed he would not sell to the Army unless the county took a hit as well—which they promptly did, save for Sally Thomas. Was Wood bluffing? The Board dared not risk it.

Since that afternoon with Wood, C-VILLE has continued to publish follow-ups on the original story, and in recent weeks radio host Coy Barefoot of WINA has taken up the cause of digging into the details of the May 2006 resolution and the developments that prompted it. After one recent show on the subject, Wood called in and gave a statement since publicized by Charlottesville Tomorrow, a local nonprofit development watchdog. When asked by Barefoot if he was getting preferential treatment, Wood responded: “I think I deserve special treatment. I pay millions of dollars in taxes. In reality, I think I do get special treatment, negative treatment. I truly believe I get negative treatment as a developer in this community.”

Part of the Board’s motivation for voting for the resolution involved another proposed land change, this one from Development to Rural. One late afternoon in spring ‘06, a local landowner, Clara Belle Wheeler, received a phone call from Supervisor Ken Boyd, asking if she was still interested in a conservation easement for her land as she had indicated to supervisors in the past. “I remember thinking, ‘Why is he calling me at 4:30 or 5?’” Wheeler says.

She says she told him she would think about it, but Boyd went away from the conversation with a different impression, allowing him to present the Board with a setoff of 77 acres that would be moved out of the growth area. Unbeknownst to Wheeler, her land made its way into the resolution a day before the vote. “We all know that when you want something very badly you frequently hear what you want to hear,” Wheeler says, offering an explanation for Boyd’s misunderstanding.

When my C-VILLE feature was published—with a brief mention of Wheeler’s inclusion—friends began to get in touch with her, asking her about the land swap. She was shocked and enraged. Wheeler promptly informed the Planning Commission she did not want her land rezoned and the proposed adjustment was removed from the Pantops Master Plan in early June. “Changing a land designation and closing a land deal is not an emergency,” says Wheeler. “It’s something you do with careful deliberate consideration, open and frank discussion and in writing. It’s not something you do with a telephone call.”

We may never know if Canar was the leak, as Wood denies it and Supervisor Ken Boyd—who was secretly warned that the deal between Wood and the Army might be falling through—will not reveal his source either. If we are to discover the identity then it will likely be thanks to Joe Graham, a local citizen who has taken it upon himself to find out some of the details.

In April, Graham filed a series of FOIA requests that have all since been denied, including one trying to find out if Canar was the source. Another recent denial involved a request for the appraisal. My own FOIA request for the appraisal was also shot down under 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(4), which entitles the government to withhold information only when that information is: (1) “commercial or financial,” (2) “obtained from a person,” and (3) “privileged or confidential.” The Army claimed that disclosing this information would harm future negotiations with Wood for additional property. With the help of The Rutherford Institute, I was able to file a carefully crafted appeal that goes at the Army’s claims in a multitude of ways. “The person handling the appeal in our headquarters office is out of the office until July 9, 2007,” an Army e-mail from June 28 informed my attorney. “When he returns, I will verify the process and time line of the appeal and let you know the status.”

C-VILLE welcomes news tips from readers. Send them to news@c-ville.com.