Jeannette Walls had an embarrassing childhood. For a storyteller, that’s gold.

She parlayed growing up with colorful, irresponsible parents—creative optimists who didn’t always provide for their children’s basic needs, like food or shelter—into The Glass Castle, her 2005 memoir that has been a New York Times bestseller for nine years.

“I had a happy childhood,” insists Walls, who now lives on a 320-acre farm in Orange. “You couldn’t pay me to go through it again.”

The Glass Castle, which sold 7 million copies in North America alone, has been translated into 35 languages and was made into a 2017 movie starring Woody Harrelson, has a devoted fan base and has become so iconic that we have to ask Walls if she ever gets tired of talking about her childhood.

“No,” says Walls. “I think it’s really not about me anymore. People are trying to figure out their own stories. People carry around so much shame or anger.”

Walls was a gossip columnist working for magazines and television in New York, and had never told anyone about living with her three siblings in a three-room house with no running water in West Virginia, about being so poor and hungry that she scrounged through trash cans for food in high school, or about her alcoholic father stealing the piggy bank that held the kids’ escape money.

One day John Taylor, a colleague at New York magazine who later became her husband, said something about Walls didn’t add up, and when he asked her about her childhood, “I always changed the subject,” she says. When she finally told him, he said, “That would make an incredible book.”

“He thought I was exaggerating,” says Walls, “until he met my mother.”

Walls describes her storytelling parents as “fabulists,” and she was thrilled when she discovered journalism and “that I could earn a salary for telling the truth.” After The Glass Castle, people started telling her their experiences, and she couldn’t go back to the snark of gossip writing. She and Taylor moved to Virginia.

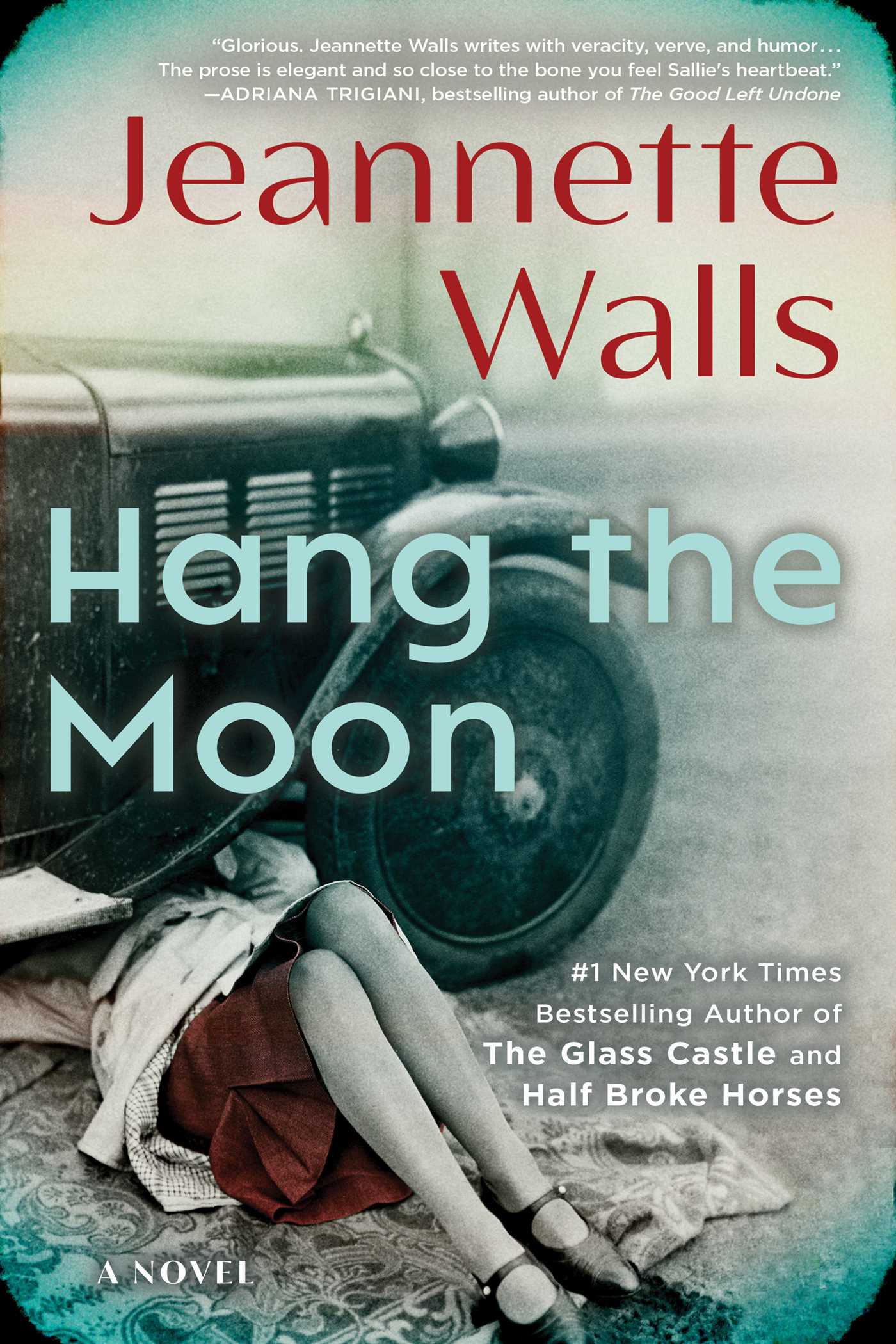

While fiction initially didn’t attract Walls, she plunged into it and her latest book, Hang the Moon, tells the story of a young woman trying to manage—and expand—her father’s bootlegging operations in Prohibition-era Virginia.

“I love transitional periods,” says Walls. The 1920s, with cars, electricity, and women’s suffrage, was such a time, moving isolated rural societies into more contact with the outside world.

“I was fascinated with Prohibition,” she says, “and with a father who was a raging alcoholic, I wanted to live through this time when you couldn’t drink.” But such efforts have unintended consequences, and for moonshiners, what had been a cash crop became illegal.

“Outlaw. Rumrunner. Bootlegger. Blockader,” thinks Hang the Moon’s heroine, Sallie Kincaid. “I don’t forget for one second what we are doing is illegal, but legal and illegal and right and wrong don’t always line up. Ask a former slave. Plenty of them still around. Sometimes the so-called law is nothing but the haves telling the have-nots to stay in their place.”

Walls relied on newspapers for much of her research. “These moonshiners weren’t keeping diaries,” she notes. She learned that Franklin County, Virginia, was dubbed the “wettest county in the world,” with an estimated 99 percent of the population involved in the business, including the sheriff.

She wondered, how was this operation run? “I spent way too long researching, but I didn’t want to put anything in the book that couldn’t happen.”

Walls also wanted to explore what it was like to be a woman in a man’s business, and Elizabeth I and her oft-married father, Henry VIII, provided a template.

“My mother and father fought over Elizabeth,” recalls Walls. “My father adored her and called her a ‘tough-ass broad.’”

Walls was reading a biography of Elizabeth with ”cousins marrying each other, people killing each other,” and thought, “They’re kind of like white trash, aren’t they?”

Transporting the powerful, murderous Tudors to 1920s Virginia had Elizabethan experts thinking it was a fabulous idea—and friends with their eyes glazed over, says Walls. Ultimately she had to make the story her own, and she assures readers they don’t need to know about Elizabeth’s rise to power to read Hang the Moon.

The book is also a story about family, and “how we take on these roles that are assigned to us,” says Walls. “It’s the story of a woman underestimated because of the circumstances of her birth.”

Family continues to remain important to Walls, and she moved her artist/hoarder mother—whom she once observed dumpster diving in New York as Walls rode by in a cab—into a cottage on her farm. “I was able to love my mother more as an adult than as a child, when I expected her to take care of me,” she says.

“I still found her maddening,” says Walls, listing the 18 typewriters and 75 cameras she found cleaning out her mother’s cottage after she died in August 2021. “But she found such joy in life.”

Appraising her parents is no longer a matter of forgiveness for Walls. “It’s acceptance.” She and her siblings had their father, Rex Walls, disinterred and reburied alongside Rose Mary Walls on their daughter’s farm.

And she inherited some of her parents’ optimism. “Life is so dang good,” she says. “It’s so ridiculously beautiful.”