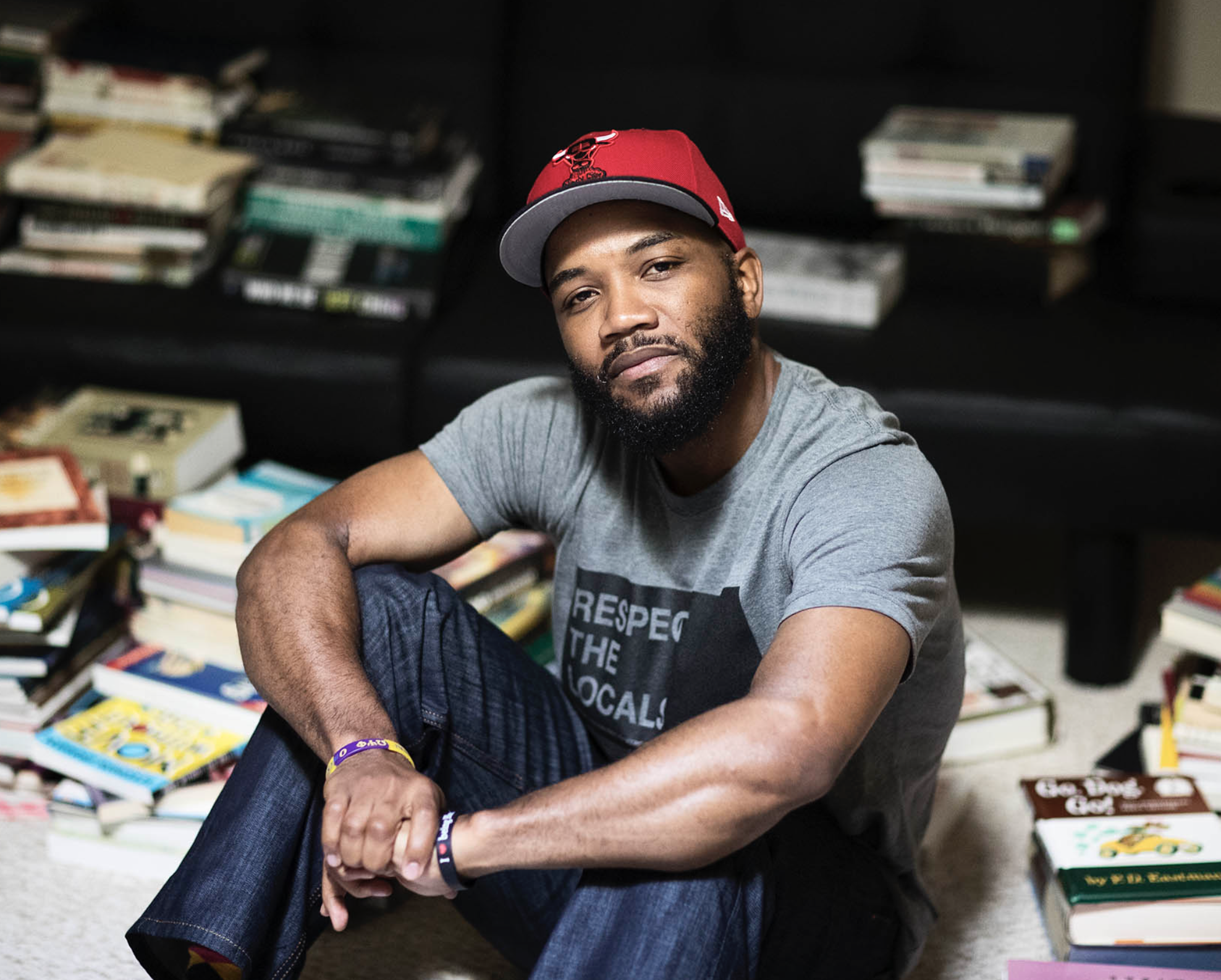

Dr. A.D. Carson is a musician, performance artist, and writer, in addition to being an associate professor of hip hop and a Shannon Center Fellow for Advanced Studies at the University of Virginia. His album, i used to love to dream, was the first peer-reviewed rap album and received UVA’s 2021 Research Award for Excellence in the Arts and Humanities, among other honors. This week, Carson publishes a new book, Being Dope: Hip Hop & Theory Through Mixtape Memoir (available November 19), which combines essays and interviews to explore his life as well as the cultural significance of hip hop.

C-VILLE: Can you describe how you use the concept of dope as both context and critique in Being Dope?

A.D. Carson: I think a lot of people ask questions about the glorification of certain kinds of characters by hip hop artists—fictional gangsters like Tony Montana from Scarface, Frank White from King of New York, or Nino Brown from New Jack City, to name a few. These ‘bad guys’ become heroes as artists adopt their images to promote a kind of American rags-to-riches story where the underdog might not come out on top, but he certainly gives the world hell while fighting to realize that dream.

My argument in Being Dope is that if we were to look at actual American history, the biggest kingpins were the founders of this country, and the products they sold, bought, and tried to scientifically engineer were people. In particular, Black people were their drug of choice. I don’t mean to imply that any of the people who were trafficked were less than human. We all know that lie was just a way to make those human traffickers feel justified in their brutality. My argument is actually the opposite of that; our humanity was never up for debate.

But seeing those historical ‘heroes’ as the archetype for a kind of American fascination with ‘drug lords’ and ‘bosses’ helps us see that it didn’t begin with hip hop culture. And these men aren’t fictional!

Similarly, many of the things that we point out in hip hop that are objectionable—violence, misogyny, sexism, materialism, and especially the relationship to drugs (legal and illegal)—are things that the United States values, and hip hop is being scapegoated as the cause of it. More accurately, hip hop, as a facet of American culture, often reflects American ideas and ideals.

The violence of academic institutions serves as a refrain in the book, examined through your time as a graduate student at Clemson and as a UVA professor. How do you hope Being Dope contributes to conversations about academia’s structural violence as well as the ongoing work of trying to dismantle the colonialism that undergirds these institutions?

I don’t have much hope that we will be able to successfully decolonize the colonies, but I do think that we can be mindful of the ways we navigate them and try not to perpetuate the harm that we know gets done regularly by institutions, even while we are studying or working at them.

If Being Dope can add anything to those conversations, my hope is that it provides some clear models for what that work can look like while not pretending to offer easy solutions and that it also connects the present to the past so that folks who are reading know that the work has been ongoing—it predates right now, it also predates me and the things that happened in Clemson and Charlottesville between 2013-2025, and it also predates the 1970s when hip hop was taking shape as a cultural movement.

You write, “Grief is always there, and it often dictates the perspectives of my work… The persistence of Black death… its inescapable presence is sometimes there explicitly but often unnamed.” Indeed, personal and collective grief are woven throughout the book. How can hip hop serve as a survival tool?

I think that hip hop (and music more generally) works as a cultural inheritance of sorts. Seeing it in this way, it’s easier for me to hear and engage with people from my past who are still present through music-making and memory in ways that help me know they aren’t really gone just because they aren’t here physically anymore.

Music also gives me ways to tap directly into the pasts that I’ve inhabited, like writing about the near-fatal car accident I caused when I was writing my first book, COLD. In Being Dope, I’m able to revisit that event and that time period through my own music and music from other artists that have helped me through difficult times, which included mental health crises. Music isn’t therapy. I’m sure that’s written in the text of the book. But it can certainly be therapeutic.

What’s your hope for how this book lives in the world?

I hope people see the book as a way into many of the conversations that we continue to avoid because we think they’re too complex, complicated, or awkward. This includes talking about race, gender, drugs, education, mental health, politics, religion, and so much more. Music is a common text that we all continue to engage with despite all the things competing for our attention and commitment. It’s as useful a tool as any for generating discussion if it can create a foundation upon which to build conversationally or artistically, or in any of the many ways we might build with one another.