The Appalachian narrative has always been molded by outsiders. From the carefree yokels of Li’l Abner to the crumbling coal-mining towns of National Geographic, the popular image of Appalachia has long been one of simplicity and economic decline.

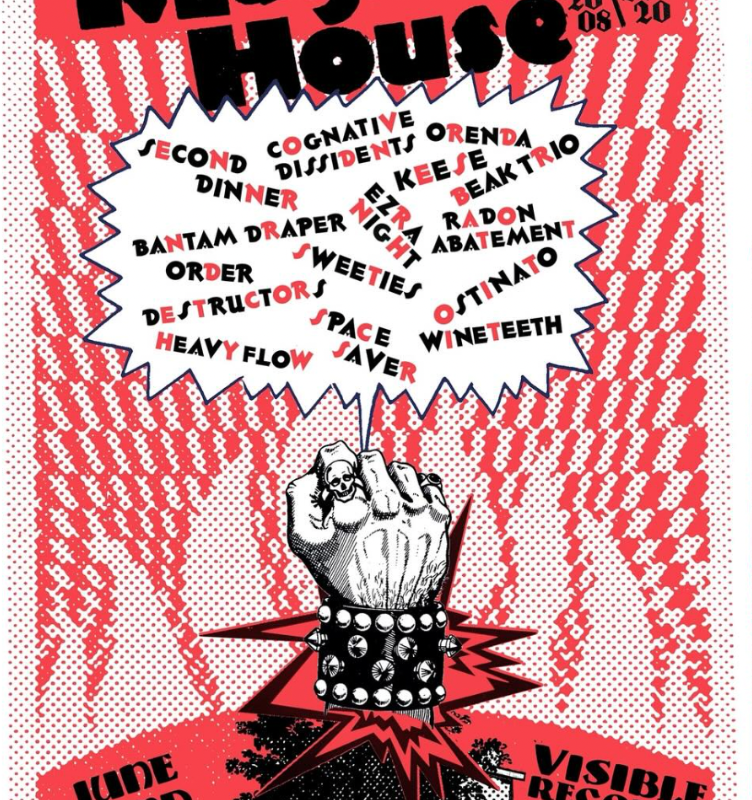

)/blogSternfamily-725190.jpg) Four Kentucky miners photographed by Andrew Stern, whose “Appalachian Portfolio” is on view through October at the Bridge/PAI.

|

Modern Appalachian poverty came under national scrutiny in 1964, when documentary photographer Andrew Stern’s pictures were included in the Senate hearings for Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty program. From 1959 to 1963, Stern traveled to Harlan County, Kentucky, to photograph residents, generating over 900 images that he would eventually use in an Emmy-nominated documentary for PBS. Once his pictures were widely published in the early ’60s, magazines like Life and Look followed up with sensational features on poverty in rural Kentucky, and their characterization of the region lingers.

But despite the role Andrew Stern’s photographs played in sparking public debate, they aren’t pictures of poor, benighted hill folk. As University of Kentucky Archivist Kate Black writes, “his body of Appalachian work does not contain a single photograph of a soiled child pressed against a dirty window peering forlornly out to a world she can’t dream of inhabiting.” Stern’s “Appalachian Portfolio,” on view through October at The Bridge/PAI, is a rare glimpse of mid-century rural life in America, without the exoticizing skew of an exposé.

What first brought you to Harlan County, Kentucky?

I was working in Washington at Voice of America and I saw an article in the New York Times by a later Pulitzer Prize–winning photographer of the dire situation in Harlan County. So I just decided to go down there. I had a few friends in Washington who were friendly with people in the Kentucky labor movement, so I spent a few weeks in Harlan County shooting a lot of photos of the miners and their families, and when I came back there was great interest in them.

Your website has a short gallery of color photos from a return trip to Kentucky in 2008. Why did you return 48 years later?

I was invited by people in Whitesburg. I didn’t have much time, but I spent a couple of days with some of the people there and we tried to find a few of the locations that I had shot. I did make prints from that trip, but I decided not to show them with the old black and whites because somehow it didn’t work aesthetically. I could’ve shot the return photos in black and white, but I thought that would be sort of pretentious.

How different were things nearly half a century later?

Well, I was nearly half a century older. Of course, the coal industry is changing very rapidly. Mountaintop strip mining continues, but I wasn’t able to really photograph that because you need a helicopter for that. The most interesting thing I heard from the two people who drove me around was about drug use in the region. I didn’t really have time to do that story, but apparently a lot of people are hooked on Oxycontin, and there’s a thriving drug trade where the older people get a certain amount every month over Medicare and sell what they don’t need. Apparently Diane Sawyer went down and did a kind of weepy story about people who drank so much Mountain Dew that all of their teeth fell out, but I don’t know how true that was.

Is photography an honest medium? How does one draw the line between dignified and exploitative?

Let me put it this way. There are some photographers who have gone back in recent years and taken very dramatic black-and-white pictures, or posed people in a certain way to draw a certain effect. I think what people liked about my pictures, then and now, is that I didn’t go down to say, photograph poverty, and I didn’t go out of my way to make people look particularly poor or haggard.

On my third or fourth time down there I took my wife, and when we arrived in Whitesburg, Life magazine arrived at the same time to do an essay on poverty. So we all had dinner that night, the two of us and the writer and photographer they sent down. We talked about what we were going to shoot the next day, and I said we were going to shoot the one-room schoolhouse. Well, Life was also planning on shooting it, so of course, we flipped for it. We lost, and so the next day Life had to drive 25 miles to reach it, and they brought a Jeep because the roads were terrible. Well, Harry Caudill, the author of Night Comes to the Cumberlands, invited us all to dinner that night. My wife and I showed up first, but eventually the team from Life stumbled in, complaining about their really harrowing day on the muddy roads. And Caudill said, “I hope you gentleman were successful in your search for poverty.”