One of the biggest stories that shocked America 100 years ago—about a farm in Georgia where Black people were essentially enslaved and at least 11 men were murdered—is pretty much forgotten today.

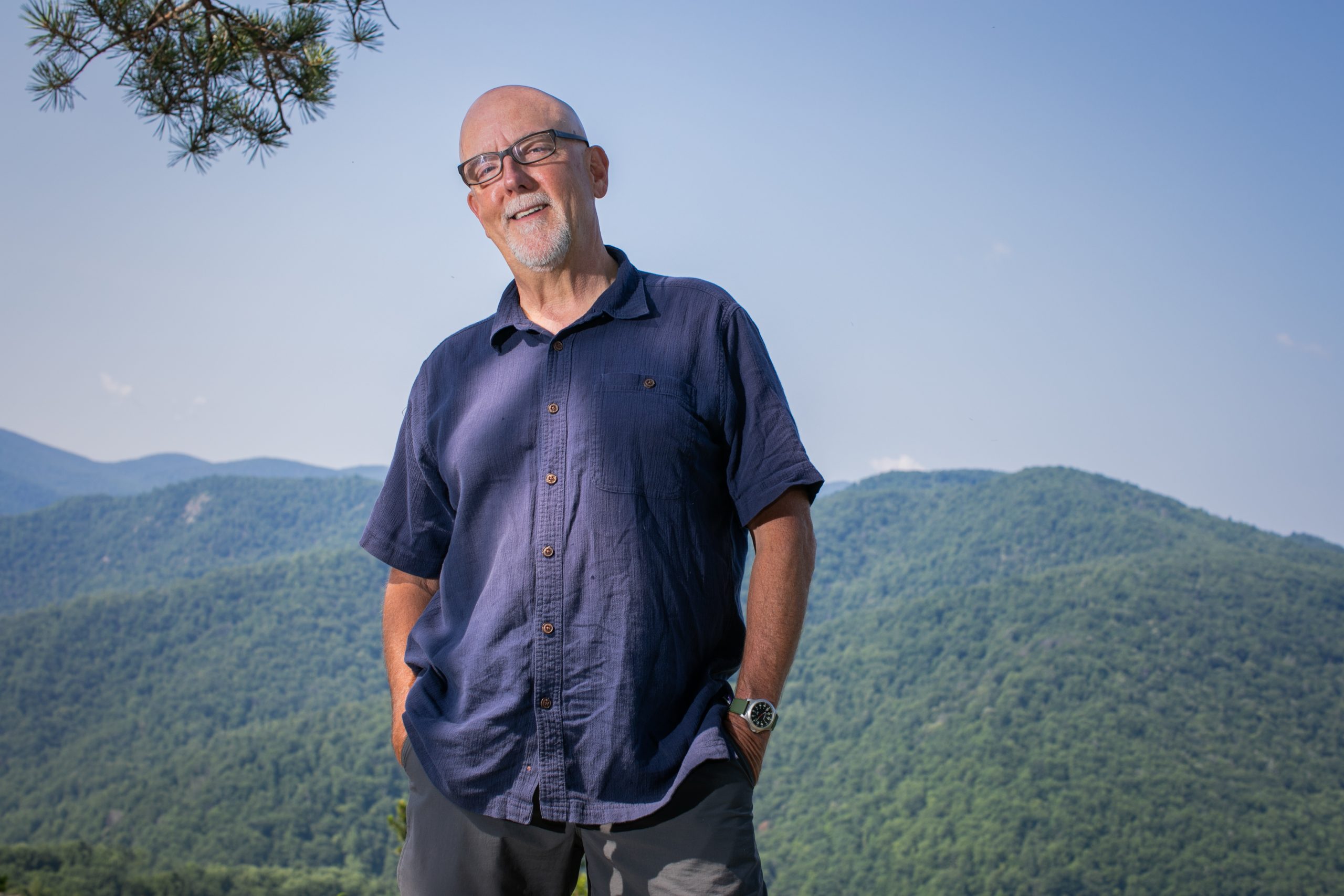

That will change with Earl Swift’s eighth book, Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America’s Second Slavery, which was published April 2.

Swift was scanning microfilm in the Old Dominion University library, looking for a brief mention of the 1921 passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act—”which is now recognized as the most important piece of highway legislation in American history,” he says—for his book The Big Roads, when he ran across this front-page headline in the March 27, 1921, New York Times: “Find Nine Bodies in Georgia Peonage Murder Inquiry.”

“I had never seen the word ‘peonage’ in print before,” he says. “I knew nothing about this story.”

That was in 2007 and he couldn’t forget it. Over the next 17 years, Swift did research when he could to tell the story of John S. Williams, who owned a cotton farm in remote southeastern Georgia. Williams and his sons would find Black men who’d been arrested for crimes such as loitering, pay their $5 fine, and force them to work to pay off their debts. The men were whipped, hunted down if they fled, and ultimately murdered when federal agents got wind of the operation.

While Jim Crow thrived in the 1920s, America was appalled that more than 50 years after the Civil War, African Americans were still in bondage. Williams wasn’t the only one subscribing to peonage at the time, but the cruelty of the murders of men who could testify against him stood out.

A young boy playing at Allen’s Bridge along the Yellow River made a grisly discovery on a Sunday morning in the spring of 1921: Two drowned men were bound together with wire and chain, and weighed down with a 100-pound sack of rocks. Another turned up in a nearby river, then another and another.

Swift recreates the criminal trials that gripped America. Through court transcripts, archival research, and many trips to Georgia, he paints a vivid portrait of the country at that time, and how both the notorious murderers and the heroes of the case are mostly forgotten today.

There’s James Weldon Johnson, who led the NAACP in pursuing the case and seeking anti-peonage and anti-lynching legislation, while at the same time playing a key role in the Harlem Renaissance. “James Weldon Johnson ought to be a household name,” says Swift.

There’s Walter White, not the character from “Breaking Bad,” but a man who identified as Black, but could easily pass as white—and did, traveling to the many sites of racial massacres to report for the NAACP, which he later led. “He had ice water in his veins to go to Tulsa,” says Swift.

And there’s former Georgia governor Hugh Dorsey, whose obituary noted that he had been a prosecutor in the notorious 1913 trial of Leo Frank, who was lynched by a mob outside Marietta. Dorsey seemed to try to redeem himself as governor, quietly supporting the prosecution of Williams. When the NAACP wrote him, says Swift, “Against all custom of the day, he answered.”

Even knowing the basics of the horrific case, there were still aspects that shocked Swift.

“The pervasive and casual use of the N-word by all walks of society, no matter where they were,” he says. “That was a hell of a shock.”

Lynching was part of the landscape of the early 20th century, targeting not just Black individuals, but communities as well. Swift was appalled at “the brazenness of the violence against Black people, at times done with seeming impunity, as if it were a God-given right.”

But the most shocking? “That anybody could be as wantonly cruel as John S. Williams,” says Swift. He believes Williams likely could have gotten away with the murders if he’d killed and buried the men on his land. “These were guys who wouldn’t be missed,” he says.

Instead, “with unnecessary depravity,” Williams told the men he was sending them home—“the nastiest touch of all,” says Swift—drove them to nearby rivers, where he tied them up and threw them into the water.

Today, there’s no trace of the horrors that took place in Jasper and Newton counties. The Williams farm has disappeared into the overgrown landscape, except for a few rose bushes that stood in front of the house. Even the paupers’ graveyard, where the victims were buried, can no longer be found on Jasper County government land.

The word “peonage” also has pretty much disappeared, but it’s still around. “Not all human trafficking is peonage,” says Swift, “but all peonage is a form of human trafficking. It changed form quite a bit and now targets a different kind of victim, often immigrants.”

Turtle Cove is a Georgia subdivision of lakeside homes on land that used to be farmed by Williams’ son Hulon. Swift thinks it’s unlikely current residents are aware of what happened there. Looking down the golf course fairway “is such a jarring contrast to what you know happened a century ago,” he says. “It’s mind boggling.”