The University Police Department and National Organization of Black Law Enforcement hosted a procedural justice workshop, titled Policing With Our Community, at UVA on October 26. The event provided insight into not only the ways in which police departments could improve their relationship with the communities they serve, but also foster trust and loyalty within their internal structure. UPD officers and staff, two former FBI agents, and many university students and professors attended the free gathering.

Former UNC-Chapel Hill police chief David Perry, a speaker for NOBLE, described the ways in which police officers have come “together all over the country to advance their partnership with communities.” He explained 21st-century policing and how it is driven by procedural justice—“it helps the root system grow,” he said. Through examples taken from various facets of college and police life, he demonstrated the importance of transparency and impartiality when it comes to the implementation of policies.

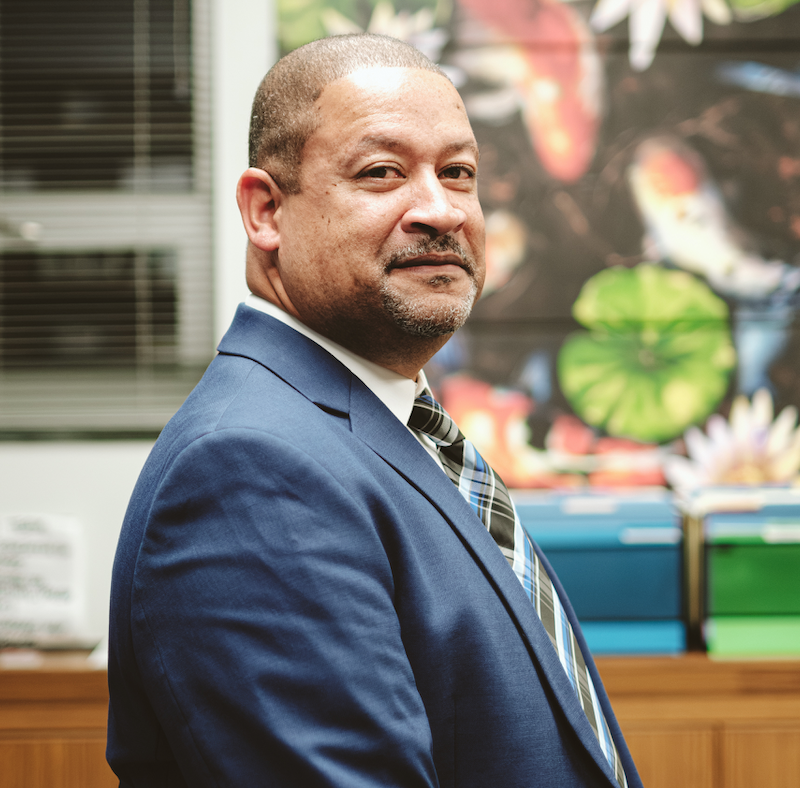

NOBLE’s Robert Stewart, who worked for the Washington, D.C., police department for nearly two decades, provided attendees with a better understanding of the day-to-day operations of a police department, stressing that “cliques” within police departments can obscure accountability for officers. He asserted that this problem is not just limited to white-dominated police departments.

“We had Black chiefs who promoted their friends and couldn’t discipline them,” Stewart said.

Stewart also emphasized the importance of educating police officers before they pick up their badge and gun. He suggested that a solution to constant police understaffing could be to have unarmed trainee officers address and write up non-violent crime reports, such as robberies and road accidents—75 to 80 percent of all crime reports do not require being armed. This way, trainees could do the “simple stuff” before dealing with any violent crime offenses, he said.

It takes five years for new police officers to become fully educated in their profession, explained Stewart, stressing the importance of “tactical soundness” on the job, and the problems with the current promotion system within police departments. The best officers, he insisted, are often taken out of patrol to be trained in specialized units—positions that have very little interaction with the public.

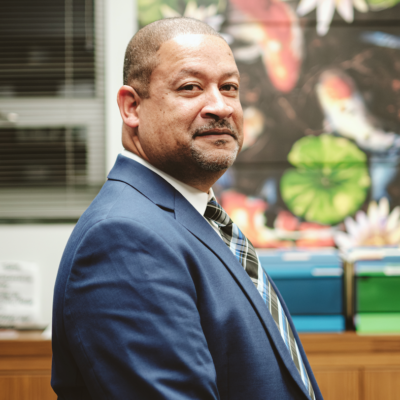

During the question and answer portion of the workshop, C-VILLE questioned UPD Chief Tim Longo about the department’s lack of transparency in the early days of its investigation into the September 7 Homer statue hate crime, during which Albemarle County resident Shane Dennis placed a noose, a weapon used to lynch Black people for centuries, around the neck of the Central Grounds statue. In the weeks following the discovery of the noose, student groups learned that the perpetrator left documents at the foot of the statue. Though UPD confirmed that the perpetrator had left items, police provided no further details, sparking widespread student protest. The university administration did not reveal until September 22 that one of the documents contained the words “TICK TOCK.”

Longo pushed back against this criticism, explaining his initial decision to keep the contents of the document private. “We keep information private that only the suspect would know. We need to be sure that they can only know that information if they were involved [in the crime],” he explained.

He argued that there must be a balance between being transparent with the community without compromising the integrity of the investigation.

Closing out the event, officers shared their stories of enjoying their decades of service, and encouraged the Charlottesville community to “come to the table” with local police departments to foster a greater sense of trust and accountability.