Since interim Charlottesville City Manager Michael Rogers and D.C.-based law firm Venable LLP presented a proposed collective bargaining ordinance last month, the Amalgamated Transit Union, Charlottesville Area Transit employees, and other union supporters have pushed back against numerous restrictions, including initially limiting bargaining to police, firefighters, and bus drivers—and keeping certain items, like health and welfare benefits, off the bargaining table.

During the September 6 City Council meeting, multiple community members urged the city to give all city employees the right to unionize at the same time, and allow them to bargain over benefits and disciplinary procedures, among other major ordinance revisions. However, several called for police to be excluded entirely from bargaining, citing the mass resistance to reforms and accountability shown by police unions across the country.

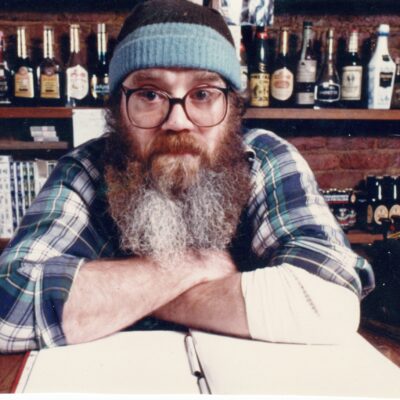

Longtime CAT driver Matthew Ray encouraged the city to use final binding arbitration—during which a neutral arbitrator makes a decision that must be honored—to resolve certain grievances and negotiation impasses, as well as allow CAT supervisors to have representation. “If you don’t have a neutral, third-party arbitrator, it’s not really a union to me,” he said during public comment.

Though the proposed ordinance permits the city and a collective bargaining unit to hire a neutral fact-finder to resolve a dispute, the city manager or council can reject the fact-finder’s recommendations. Across the city, supervisors; seasonal, temporary, confidential, probationary, and management employees; and volunteers would not be allowed to unionize. And units would not be able to bargain over health and welfare benefits, core personnel rules and decisions, and budget matters.

Daniel Summers, who has driven for CAT for over a decade, also pushed the city to speed up the ordinance’s timeline—to give the city and units time to engage in mediation and fact-finding, Venable has recommended any collective bargaining agreement go into effect on July 1, 2024, meaning employees not included in the initial three units would have to wait until 2026 to unionize.

“The way things are going right now [at CAT], things are falling apart at the seams,” claimed Summers. “You’ll have people who won’t want to work for the transit system, if they don’t see the collective bargaining taking place.”

Local resident Greg Weaver voiced concerns about Rogers’ employer, The Robert Bobb Group, and its anti-union track record—as emergency financial manager for Detroit Public Schools, Robert Bobb clashed with local unions when he outsourced hundreds of jobs to private contractors and closed dozens of schools in 2011.

Allowing police to unionize could put a stop to the city’s criminal justice reforms, like the Police Civilian Oversight Board, explained Weaver. Nationwide, police unions have prevented officers from being held accountable for misconduct, and worked to overturn reforms through collective bargaining. “The police have already shown that they are quite well organized, and that they have the power to get a police chief fired,” added longtime housing activist Brandon Collins.

Following public comment on the ordinance, Councilor Brian Pinkston voiced his support of police officers, but was hesitant to include them in the initial bargaining units. “That’s not a hill I’m going to die on [if] we decide to go forward with the police being a part of the first three, but it’s my sense that the community would prefer for the police to be later, if at all,” he said.

Councilors Michael Payne and Sena Magill pushed for the ordinance to allow bargaining over all benefits and disciplinary procedures. Payne also supported permitting non-binding arbitration for non-fiscal matters, and creating a third bargaining unit for general employees—not just police. “If there is a concern about staff capacity, we could phase it in, and limit it to transit and fire department who have come forward with pledge cards, and first-come-first-serve phase in anyone else who comes forward to us,” he said.

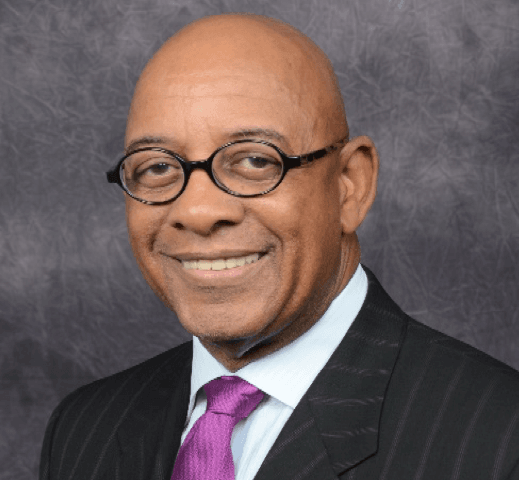

Mayor Lloyd Snook questioned whether binding arbitration over non-fiscal matters, like disciplinary procedures, would compromise the city manager’s authority to hire and fire, and pushed back against calls to ban police from unionizing, claiming that Charlottesville does not have “a history of serious police violence.”

“I don’t think that we have two classes of employees: police officers and everyone else,” said Snook. “That’s in essence what this argument becomes, to say because police officers have done bad things in the past, mostly in other places, we’re going to treat them differently.”

“Do you think those are things [about binding arbitration] that cannot be addressed while still matching what other localities in Virginia have done?” asked Payne. “And on the police point, what would you make of the argument that there’s a qualitative difference with the police because they have a monopoly on the use of the violence, and there’s no other employee that could have the legal authority to kill you?”

“The fact that a police officer carries a gun to me doesn’t change anything else about the employment relation. It doesn’t mean we give them certain rights, or deny them certain rights,” replied Snook.

Rogers and Venable will consider the community and council’s comments, and return to the councilors with an amended ordinance to vote on during their October 3 meeting.