For the last two years, Democrats have controlled Virginia’s state Senate and House of Delegates, and a Democrat has served as governor. The party has used those majorities to reshape the state’s laws. The Dems abolished the death penalty and legalized marijuana. They made it easier to vote in a variety of ways, including repealing Virginia’s mandatory photo ID law. They passed a major bill called the Clean Economy Act, which will force the state’s utility companies to start adopting renewable energy. They increased spending on education, including offering free community college for everyone in the state who makes below a certain income. They passed a moderate minimum wage increase—currently $7.25 an hour, it’ll be $12 an hour by 2024.

In order to see these reforms through, the Democrats will have to remain in power. Next month, all 100 House of Delegates members are up for another two-year term; Democrats currently hold a 55 to 45 advantage in the chamber. And former governor Terry McAuliffe is hoping to win a second term in the state’s highest office. He’s up against well-funded businessman Glenn Youngkin.

Virginia politics is old hat for McAuliffe. He was the state’s governor from 2014 to 2018. He chaired the Democratic National Committee from 2001 to 2005, and led Hilary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign. He breezed through a Democratic primary this summer. Youngkin spent 25 years at high-end private equity firm The Carlyle Group, including two years as its CEO. He spent $5 million of his own money during his primary campaign, eventually triumphing in a ranked-choice convention.

Throughout the campaign, Youngkin has emphasized McAuliffe’s insider status, trying to position himself as a new face whose business experience would help him run the state. McAuliffe, on the other hand, has tried his best to cast Youngkin as a right-wing radical, taking every possible opportunity to tie the Republican nominee to Donald Trump.

Third-party candidate Princess Blanding will be on the ballot as well, running under the Liberation Party. Blanding’s brother, Marcus-David Peters, was killed by Richmond police in 2018, and Blanding hopes to enact a variety of progressive criminal justice reforms, including ending qualified immunity for police officers, something both McAuliffe and Youngkin oppose.

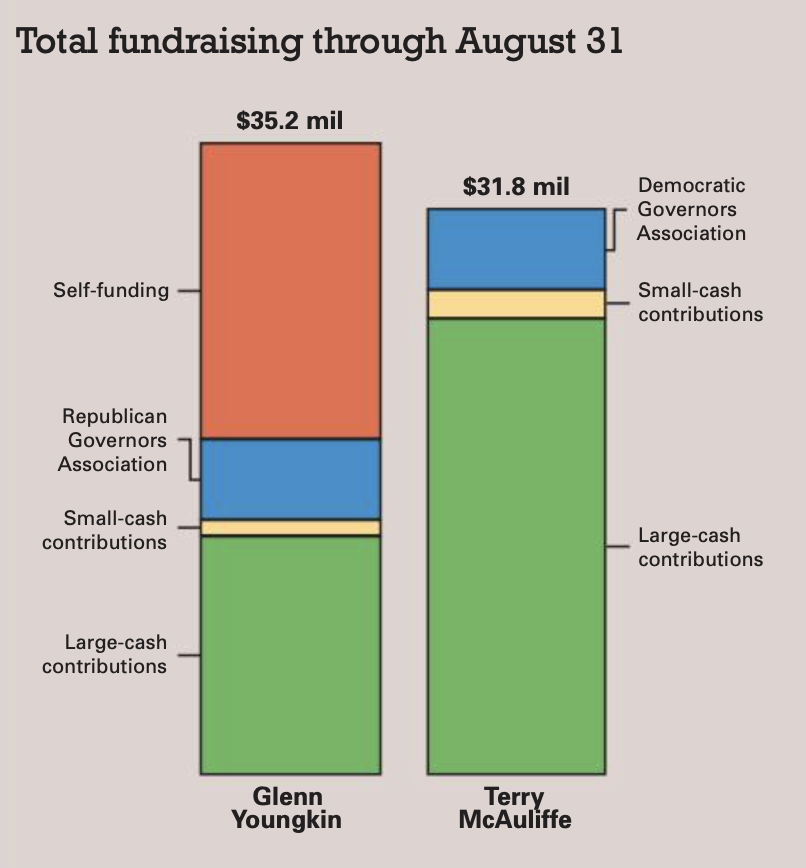

Both major party candidates have raised huge amounts of money—each had eclipsed the $30 million mark by August 31, a full two months before election day. In July and August, McAuliffe pulled in $11.5 million and Youngkin added $15.7 million to his chest. By contrast, four years ago Ralph Northam and Ed Gillespie raised $7.4 million and $3.3 million, respectively, during the July and August filing period. Both candidates have raised the vast majority of their money from large donations.

The candidate who has raised more money has won the last three Virginia gubernatorial elections. Tim Kaine’s 2005 victory over Jerry Kilgore was the last time a financial underdog won.

Democrats have triumphed in every statewide election in Virginia since 2012. In 2017, Ralph Northam won by nine points, and last year Joe Biden won the state by 10. This election will be a test of just how blue Virginia has become—midterms traditionally see votes swing back toward the party that lost the most recent presidential election. If McAuliffe can weather the Republicans’ midterm bounce, it’ll bode well for future Dem dominance in Virginia.

FiveThirtyEight’s poll aggregator shows McAuliffe with a slight edge over Youngkin, polling at 47.6 percent to the Republican’s 45.1 percent. RealClearPolitics’ aggregator shows McAuliffe leading 48.5 to 45.0. The election takes place on November 2. Early voting is now open.

The Issues

Education

McAuliffe has campaigned on raising teacher pay and expanding public preschool options. At the second debate, he said, “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach,” a quip the Youngkin campaign has seized on.

Youngkin has parroted national Republicans’ promises to ban critical race theory in schools. He’s said he’ll direct the Department of Education to protect advanced math classes and other academic tracking practices, and create 20 new charter schools.

Elections

Restoring voting rights to 173,000 felons was among the signature achievements of McAuliffe’s first term. Now, he hopes to go a step further, enshrining automatic restoration of voting rights in the Virginia constitution.

Youngkin dragged his feet in accepting the results of the 2020 presidential election, before admitting that there wasn’t “material fraud.” He wants to launch an Election Integrity Task Force, which would include requiring IDs to vote and the purging of voter rolls monthly.

Health care

McAuliffe wants to strengthen Medicaid and enlist federal money to lower health insurance premiums. He also says he’ll work to put Roe v. Wade abortion protections in the Virginia constitution, making it more difficult to overturn down the line.

Youngkin opposes the state’s recent Medicaid expansion, and has gone so far as calling the expansion “sad.” He has described himself as “unabashedly pro-life,” and says he’ll tighten abortion laws if elected.

Environment

McAuliffe hopes to accelerate Virginia’s transition to clean energy, aiming to get the state to 100 percent clean energy by 2035. Along those lines, he says he’ll restructure the state’s regulatory system to incentivize clean energy innovation.

Youngkin’s economic plan includes suspending the state’s gas tax. He opposes the Virginia Clean Economy Act, which Democrats passed last year, and has said that a renewable-energy-focused economic overhaul is not “doable.”

Criminal justice

McAuliffe initially suggested he would be open to ending qualified immunity for police officers, but walked that statement back at the first debate. McAuliffe says he’s never been in favor of defunding the police. He does want to invest in body-worn camera programs.

Youngkin wants to replace everyone currently sitting on the parole board, which Republicans feel has been too generous in granting parole in recent years. He also says he’ll protect qualified immunity.

Downballot statewide races

Alongside the McAuliffe vs. Youngkin clash, voters will also choose between Republicans and Democrats for lieutenant governor and attorney general.

Virginia’s lieutenant governor is essentially the vice president of the state, serving as the tie-breaking vote in the state Senate and the first in line for power should the governor become incapacitated. Additionally, five of the last 10 LGs have later become governor.

The Republican nominee for lieutenant governor is Winsome Sears, a Marine who served as a state delegate from 2002 to 2004. Since deciding not to run for reelection, she’s sat on the Virginia Board of Education, worked for Donald Trump’s reelection, and now owns an appliance company in Winchester. The Democrats are running Hala Ayala, an immigrant who’s been a delegate since 2017. This year, she spearheaded a bill requiring the Virginia Employment Commission to establish a paid family leave program by 2024. The victor will be the second woman to ever win a Virginia statewide election—Mary Sue Terry served as attorney general from 1986 to 1993.

Democrat Mark Herring is seeking his third consecutive term as the state’s attorney general. Herring has empowered his office to investigate police departments for civil rights violations, cleared the state’s backlog of untested rape kits, and defended Virginia’s new gun restrictions in court against challenges from the NRA. His Republican opponent, Jason Miyares, is currently a delegate representing Virginia Beach. Miyares’ top priorities are to “punish criminals and protect victims,” fight illegal immigration, and support the police.

These races are likely to go as the governor’s race goes. In the last decade, split ticket voting has become vanishingly rare in ever-more-polarized American politics.

In the 2008 presidential election, 83 of the nation’s 435 House of Representatives districts voted for a presidential candidate and a House candidate of opposing parties. In 2020, just 16 districts split their tickets. In Virginia, three of the four gubernatorial elections held from 1994 to 2006 saw split-ticket winners, but all of the last three victorious governors have brought their party’s lieutenant governor and attorney general into power as well. Unless the governor’s race is very, very close, expect the winner to bring his down-ballot compatriots with him.