Everything is falling apart—and I don’t mean that metaphorically. In Texas, a winter storm recently caused the power grid to fail, leaving millions without heat and icicles dropping from ceiling fans. In Jackson, Mississippi, 96 broken water mains in a 100-year-old system of municipal pipes have dirtied the water for three weeks and counting, and caused schools to shut down. Locally, with a worsening housing crisis, Charlottesville has just begun to redevelop its public housing after decades of deterioration. Oh, and there’s still a global pandemic going on.

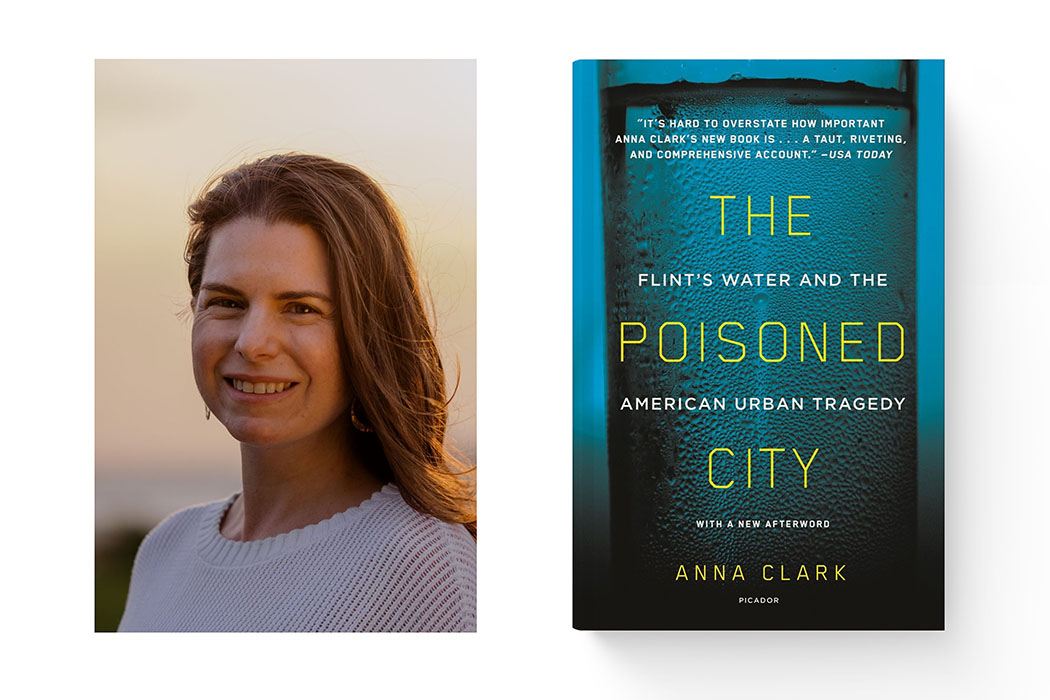

What’s going on here? Why is this all happening at once? Some answers can be found in Anna Clark’s The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, which traces the story of one of the most famous infrastructure crises of the last decade: the Flint, Michigan, water disaster, when state-level mismanagement let corrosive river water run through lead pipes, poisoning residents from their own taps.

Though the crisis in Flint “escalated in a uniquely dramatic way,” says Clark, readers of the book—especially here in Charlottesville—will doubtless see a lot of their own towns in the history of the Rust Belt city.

Clark, a Detroit-based journalist, says she was hesitant to write a book that was “ripped from the headlines,” so The Poisoned City, first published in 2018, reaches back into the past to lay the groundwork for our modern decay. It traces Flint’s rise as an auto boom town while also showing how segregated the city became. Decades of racist redlining, explicitly segregated real estate deeds, and other associated policies meant that over time, money fled to the suburbs, and Flint became “a widening circle of wealth with a deteriorating center,” Clark writes.

“We literally built our communities on a separate but unequal basis. And we did it on purpose,” she says. “Lending, development, insurance, real estate, all of that.”

And so Flint, like Texas or Jackson or Charlottesville, wound up with huge amounts of “infrastructure that was destined to suffer from neglect,” Clark writes, especially in poor communities, rural communities, and communities of color. And “neglect, it turns out, is not a passive force in American cities, but an aggressive one.”

Thus we arrive at these all-too-predictable American crises. Turning the tide, Clark argues in the book, will require proactive measures. Neglect is an aggressive force, and so attempts at redress must be aggressive, too.

“It’s no longer legal to put toxic lead pipes in a drinking water system,” she says. “But there’s been no meaningful effort to remove the ones that are already there. It’s continuing to poison people.”

The pipes won’t dig themselves up. If Flint sounds familiar to you, I suggest you grab a shovel.

Anna Clark will participate in the Environmental Injustice: Reckoning with American Waste panel on March 20 at 7pm.