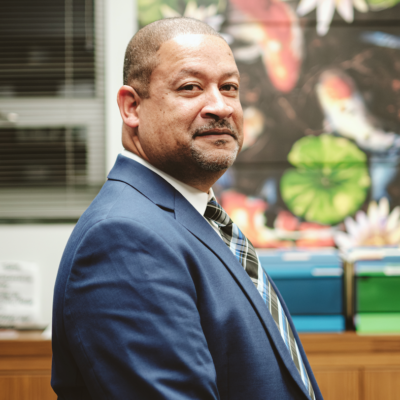

Charlottesville resident Jordan McNeish knows the perils of opioid addiction first-hand.

Three years ago, he was on an East Coast road trip with his ex-girlfriend, and the plan was to end up in Maine. But their first stop was Baltimore, to buy heroin. McNeish, 29, says he had gone from using heroin once or twice a year to “more than I would like.”

He bought 10 bags of “Scramble,” “basically a mixture of fentanyl and low-grade heroin cut with god-knows-what,” and shot up in a Burger King parking lot. The next thing he remembers is waking up covered in the orange drinks his ex had spilled while trying to resuscitate him. An EMT had revived him using two doses of naloxone, a drug designed to rapidly reverse an opioid overdose.

“The paramedic that revived me said she thought I was done,” he says.

Naloxone saved his life. Now, he wants to make sure others have the same chance.

Charlottesville has been largely shielded from the opioid crisis, with only six overdose deaths from prescription opioids reported from 2011-2017 (compared to roughly 500 a year, statewide). But the epidemic has still touched local lives, especially as it shifts from prescription opioid abuse to heroin and fentanyl (a synthetic opioid that is often mixed with or sold as heroin, but is 50 times more powerful).

In Virginia, overdose deaths from heroin and/or fentanyl have increased from 153 in 2011 to 938 in 2017, mirroring a nationwide trend.

Charlottesville reported zero heroin deaths in 2011 and 2012, but experienced 13 over the following four years, including four in both 2016 and 2017.

Twenty-five-year-old Betsy Gilbertson was among those who died in 2016. Loved ones said the free-spirited music-lover had been clean for months before her fatal overdose.

McNeish had been friends with Gilbertson when they were teenagers, but had fallen out of touch with her. He found out about her death when he read her obituary in the Daily Progress.

Still, he continued to use. “It is hard to learn a lesson vicariously when it comes to addiction,” he says. “You always have to learn for yourself.”

Eventually McNeish, who had shot heroin the day after his overdose in Baltimore, got serious about quitting.

“I started getting really angry about drug use,” he says. “Started being a fascist about being around drugs, and I would get mad when they were around me.”

He made it a week, a month, two months, and then just kept going. “The longer it had been, the easier it was to continue not using,” McNeish says. He’s now been clean for over a year.

“Some people will hit rock bottom and they’ll just turn around and never use drugs again,” he says. “It just took me three or four tries.”

McNeish funneled his energy during withdrawal into looking for ways to help others who were addicted. He was inspired by the non-judgmental stance of places like Youth on Fire, a drop-in center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the New England Users Union, a harm reduction group in which current and recovering substance abusers work to keep each other safe–even if they’re not yet ready to quit.

Along with his girlfriend, Morgan Freegan, McNeish started his own group here in Charlottesville, Jefferson Area Harm Reduction. They distribute naloxone to users who need it, many of whom they know personally. But they are limited by what they can get for free from the Health Department, and by their work schedules and daily lives.

When a public health emergency was declared in response to the epidemic in 2017, the Virginia Department of Health made naloxone available for free to the public. (It can be bought over-the-counter, but even a generic costs $20 to $40 per dose).

“The fact that anybody can get it, that means it’s out in the communities,” says Dr. Denise Bonds, health director for the Thomas Jefferson Health District. She oversees the distribution of naloxone at the Virginia Department of Health in Charlottesville, and says EMTs in the district have been using it for a few years now.

Those interested in acquiring naloxone must attend a one-hour training session, held on the first Wednesday of the month. They can then pick up two doses per week at the Health Department. But McNeish argues that the treatment should be more available and anonymous. “Someone that’s using and still driving around with drugs in their pocket is going to have a hard time going to the Health Department, sitting through a one-hour training, and even doing paperwork,” he says. In December, he asked City Council to consider starting a group similar to his to help distribute naloxone.

In addition, McNeish wants the city to look into a needle exchange program to fight the spread of Hepatitis C and HIV that is prevalent in those using intravenous drugs.

“There’s virtually no place to get clean needles,” says McNeish, who contracted Hep C himself but has since been cured. “I’ve seen people use dirty or broken syringes because they don’t have a clean one.”

Currently, the state has only authorized needle exchange programs in the districts with the highest rates of Hepatitis C and HIV, so our district can’t legally distribute syringes. But Bonds says the community is “fairly well-resourced” when it comes to addiction treatment.

Addiction Recovery Systems, Region Ten, and a handful of other facilities now offer medication-assisted treatment, a proven approach that uses drugs like methadone and buprenorphine to relieve addicts’ withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Region Ten also recently opened the Women’s Center at Moores Creek, which has 12 inpatient suites and offers the opportunity for women to keep their young children (under age 5) with them while they receive treatment.

These options allow substance abusers to regain stability in their lives, advocates say.

It’s support that may be increasingly needed. “It has gotten worse here in the inner circles that I’ve been in,” McNeish says of heroin users. “One out of 10 might die in the next couple of years in that using community.”